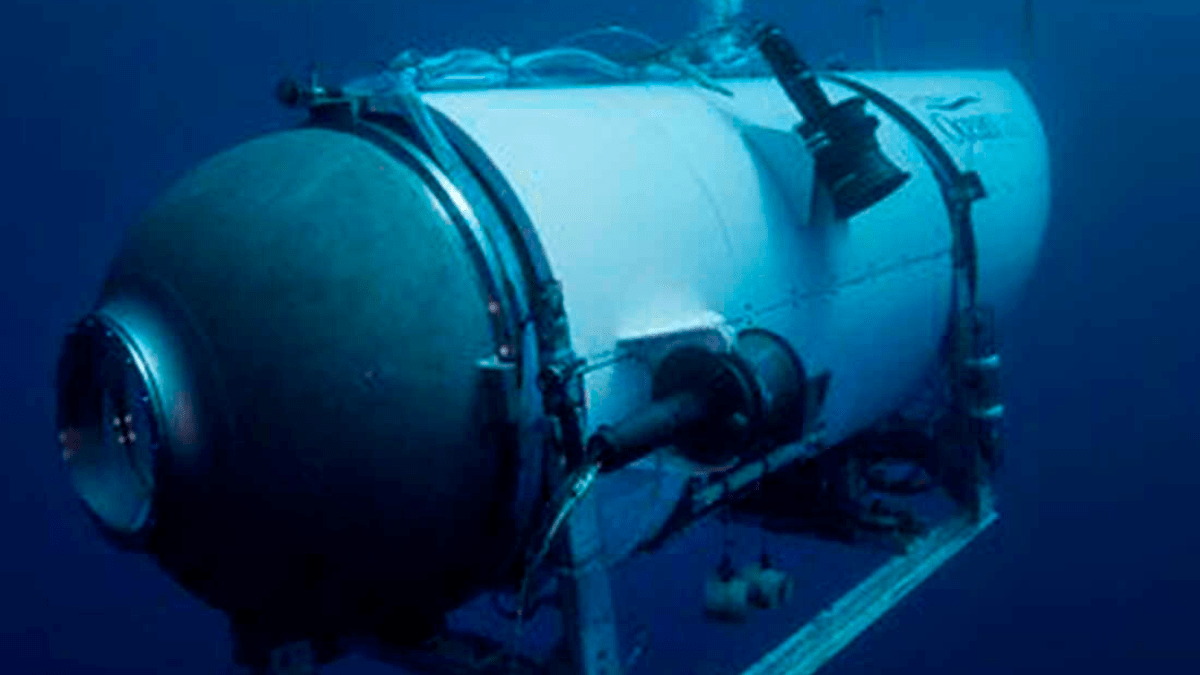

Now that we know the unfortunate fate of the five people on board the Titan submersible that imploded near the bottom of the ocean while attempting to explore the wreck of the Titanic, the focus is now shifting to the craft’s safety measures — or lack thereof.

As it turns out, those regulations were much more lax than they should have been and certainly were a huge factor in the fatal accident, which cost each passenger $250,000 to experience. On Thursday, the U.S. Coast Guard revealed it found the sub’s pressure chamber and various other detritus from the implosion on the ocean floor, confirming the unfortunate outcome.

It turns out that OceanGate, the company behind the submersible, did not follow or seek standard safety regulation protocols, and it made passengers sign a lengthy contract saying the vehicle “has not been approved or certified by any regulatory body, and could result in physical injury, disability, motion trauma, or death,” per a CBS Sunday Morning report.

What makes this all sound worse is these issues were present from the very beginning. In 2018, per The Independent, an OceanGate employee named David Lochridge reportedly shared troubling design issues with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. As a result, he was fired.

In a wrongful termination suit, he claimed he was fired for shedding light on these issues. In the suit, Lochridge said he shared the ship’s troubling safety issues with CEO Stockton Rush, saying there were “visible flaws” in the ship’s hull, flammable materials onboard, a window that wasn’t rated for the depth required, and that he wasn’t able to view safety documents about the sub.

“Now is the time to properly address items that may pose a safety risk to personnel,” the suit claimed he said. “Verbal communication of the key items I have addressed in my attached document have been dismissed on several occasions, so I feel now I must make this report so there is an official record in place.”

Lochridge said he wanted independent regulators to come and see the craft and refused to sign off on manned testing without more stringent testing of the ship’s hull. Instead of acquiescing to his demands, OceanGate fired him. That same year, more than three dozen marine professionals in the Marine Technology Society, including oceanographers and explorers, wrote a letter to OceanGate prophesying “catastrophic” issues if the sub started being used commercially. Turns out they were right.

One of the biggest issues was the fact that OceanGate was not getting the vehicle tested or rated by any outside parties, a decision that gave the experts “unanimous concern.”

“While this may demand additional time and expense,” they said in the letter, “it is our unanimous view that this validation process by a third party is a critical component in the safeguards that protect all submersible occupants.”

“The vast majority of marine (and aviation) accidents are a result of operator error, not mechanical failure,” the letter said. “As a result, simply focusing on classing the vessel does not address the operational risks. Maintaining high-level operational safety requires constant, committed effort and a focused corporate culture – two things that OceanGate takes very seriously and that are not assessed during classification.”

Rush’s response? He told Smithsonian Magazine that regulations for submarines were holding back the industry.

“There hasn’t been an injury in the commercial sub industry in over 35 years. It’s obscenely safe, because they have all these regulations,” he said. “But it also hasn’t innovated or grown – because they have all these regulations.”

By 2020, even Rush had to admit there were some issues with the hull, and it was downgraded to a depth hull rating of 3,000m (1,000m less than the depth of the Titanic). However, by 2021, the sub was making trips down to the wreck, with various issues popping up, like battery problems, per The New York Times.

When a CBS News reporter went on the sub, they said it was equipped with components that were “off the shelf,” like lights from a camping store. The sub also lost communication with the mother ship for about three hours.

Rush perished in the accident along with Pakistani businessman Shahzada Dawood and his 19-year-old son Suleman, French diver Paul-Henri Nargeolet, and billionaire Hamish Harding.

U.S. Coast Guard Rear Admiral John Mauger said the implosion probably happened early in the dive.

“This is an incredibly unforgiving environment out there on the seafloor,” he said.

Published: Jun 23, 2023 01:54 pm