The topic of banned comic books has arguably never been more relevant than it is today. It seems like everywhere you look on the news, there’s another story about a graphic novel being banned in some capacity or another.

All of this commotion has inspired me to put together a list of banned comic books that I have enjoyed in the past and would absolutely recommend to any enjoyer of such literature. In addition, some of the entries on the list are also books I haven’t read yet, but discovered through my research, and I am including them here based on recommendations from pro-literacy groups who fight against the practice of banning books. Keep in mind, these are in no particular order.

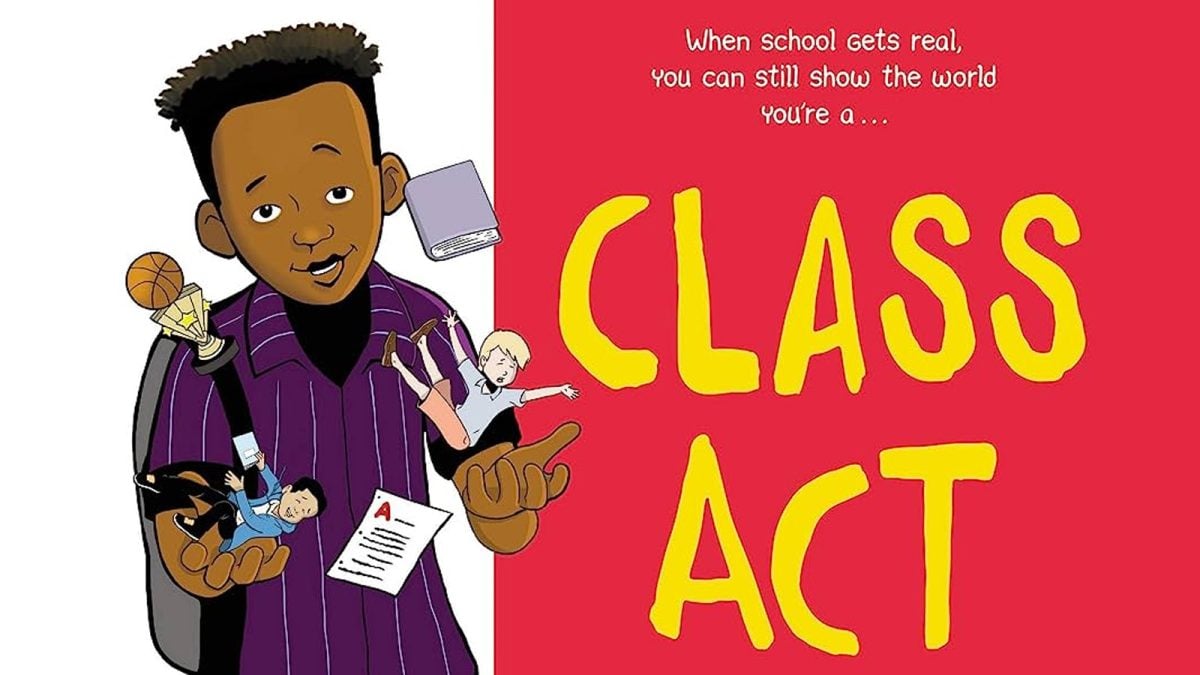

New Kid and Class Act by Jerry Craft

When I picked up Class Act a couple of years ago back at a bookstore I used to work at in Alaska, I chose the book because the character on the cover was the spitting image of a loved one of mine, so I bought the book for him. On my plane ride back to Oregon from being on vacation, I read the entire book in one sitting, and it was one of the most entertaining reading experiences I had in recent memory. The humor in the book, chock-full of pop culture references of everything ranging from Marvel to Attack on Titan, had me laughing out loud on the plane.

I found out later that the book, along with a previous installment in the series, New Kid, had been the subject of school district bans in a couple of different states. This apparently had to do with paranoia about the so-called “critical race theory” messaging in the book. According to Craft in later interviews, he wasn’t even aware of what critical race theory was when he wrote the books.

In truth, Class Act represented to me a heartfelt depiction of how Black kids can sometimes feel alienated in a white-dominated culture, as well as the various challenges associated with navigating such a world in an accessible, sometimes humorous, and age-appropriate way for late-elementary-to-middle-school-aged kids. As a white man, I often take for granted that I can look around me and see many other people who look like me at any given moment. But children of color making their way through homogenous cultural institutions don’t always have that same sense of comfort. And Class Act helped me to further understand that perspective.

I’ve started reading New Kid, which has the impressive accolade of being “the first graphic novel to win the Newbery Medal,” as Craft put it in a statement to the American Library Association (via Comicsbeat.com), and I look forward to continuing reading his work. Craft’s newest book in the series was released a couple of months back and is called School Trip (which I also plan to read).

The Complete Maus: A Survivor’s Tale by Art Spiegelman

Back in middle school, I was just getting into the more adult comic books (also called graphic novels) I would always see my older siblings read. For instance, over the course of what I believe was a single summer, I read The Dark Knight Returns, the Sandman series (more on that later), and Wolverine: Origin.

It was also during my middle school years, though not that same summer, that I read both volumes of Art Spiegelman’s seminal Maus, the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography based on the author’s interviews with his father recalling the horrors of the Holocaust as a survivor. It’s impossible not to have certain images from the book burned into my memories. But sadly, the astounding work has faced bans at various school districts in different parts of the U.S. in recent years.

While the book is a more mature-oriented work — a comic book intended for adults — it has tremendous educational value due to being one of the most accessible stories for understanding what happened during the Holocaust. However, bans on the book have sometimes cropped up due to educators’ occasional inclusion in the curriculum. So, if a middle school or high school teacher has made the judgment call that the educational value of the book is worth sending the child home with a permission slip for the parent — like you would for a documentary, say, about World War II that deals with similarly heavy themes — I can personally get behind that, rather than an outright ban. To remove Maus, often considered the greatest comic book ever written, from libraries completely strikes me as flying in the face of the book’s warning against fascism and a dangerously slippery slope, to say the least.

The Complete Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi

I remember reading Persepolis around high school age, and it was an enlightening experience about how the country of Iran transformed during the Islamic Revolution, from the perspective of a little girl, something I knew very little about before reading it at the time. Like Maus, Persepolis is also an autobiography, bringing a personal touch to the tale of a country that began to persecute its own citizens. The book was written and illustrated by Marjane Satrapi, who also co-wrote and co-directed, alongside Vincent Paronnaud, a fantastic animated film adaptation in 2007. It also happens to be one of my favorite animated movies of all time, with the black and white ink drawings from the original text jumping off the screen. According to the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, Persepolis faced being banned as recently as last year.

Sandman by Neil Gaiman

Neil Gaiman’s Sandman is another case of a work of graphic art that helped elevate the genre of comic books to that of high art in the late ‘80s through the ‘90s. The series typifies the author’s signature penchant for mind-bending and philosophical fantasy stories that have stood the test of time ever since its release. I remember flipping through the various issues just to admire the artwork, especially the jaw-dropping cover art by Dave McKean, as a child, owing to having older siblings with a massive comic book collection at the time. When I got older, I finally read all the issues I could get my hands on in that collection one summer. And I am so glad I did.

If you have a fascination with the collective unconscious and wonder whether there might be a supernatural element to dreams, Sandman’s mixture of mystery, mythology, and goth-infused fantasy is the series for you. What’s more, an impressively faithful Netflix series also stands as one of the very best live-action comic book adaptations of all time. According to CBR, “The comic series and subsequent collected editions have been banned in libraries as critics cite ‘anti-family themes,’ ‘offensive language,’ and material ‘unsuited for age groups,’ especially when initially placed in the young adult section of libraries.”

Watchmen by Alan Moore

Often cited as one of the best pieces of literature ever made, Watchmen was another book whose iconic imagery was burned into my memory from a young age from flipping through its pages from one of my older sibling’s collections. Even though I would not recommend the book for children, I would still vouch for it as a piece of literature for someone mature enough to handle darker stories. Watchmen’s depiction of an alternative U.S. history, in which costumed heroes exist in the real world, and their political ramifications, encapsulates Cold War-era anxiety about the seemingly inevitable mutually assured destruction from nuclear bombs that gripped the world at the time. I first read the book in earnest in college, immediately before the release of Zack Snyder’s film adaptation, and can easily recommend it to people in their late teens as I was. Even though Snyder’s film is inferior, in my opinion, it still has some admirable qualities to it, such as largely recreating many iconic panels from the book. Watchmen was one of roughly 300 books and graphic novels that were banned from 11 Missouri school districts in 2022 thanks to a new law that was passed in that state, according to CBR.

V for Vendetta by Alan Moore

Unlike Watchmen, V for Vendetta was not an Alan Moore book that I was vaguely familiar with as a child since it wasn’t part of one of my older siblings’ comic book collections at the time. Instead, I first read the book during high school, having purchased it from a bookstore in anticipation of the forthcoming release of the film adaptation at the time. Like George Orwell’s 1984, which I later read in college, V for Vendetta is an excellent dystopian novel about a totalitarian regime in England and traces one individual’s journey toward awareness of its evils. An anarchist who wears a porcelain Guy Fawkes mask — one that would later inspire the look of the hacktivist movement known as Anonymous — is the main figurehead of the regime’s resistance. V, the mysterious main character who has been disfigured by his history of having spent time in one of the country’s fascistic prison camps, takes the young Evey under his wing to enlighten her on his acts of defiant destruction against the government after rescuing her from being murdered by the state secret police. The movie adaptation is almost just as good, but the more nuanced arc of the detective character in the graphic novel, as well as the gorgeous art by David Lloyd, definitely makes the book version worth seeking out in its own right. According to the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, V for Vendetta has faced bans in recent years.

Deogratias: A Tale of Rwanda by Jean-Philippe Stassen

Deogratias: A Tale of Rwanda by Jean-Philippe Stassen is a book full of mysteries about a normal teen, Deogratias, whose trauma from witnessing the horrors of the Rwandan genocide causes him to descend into madness and become nothing more than a vengeful ghost of his former self. The book won the 2000 Goscinny Prize for Outstanding Graphic Novel Script and faced a ban recently, according to CBLDF. After finishing the book, I was fascinated by how illuminating it was about the Rwandan genocide, something I knew very little about beforehand. Even though it’s fictional, the story did a great job of shedding some light on some of the shadowy corners of history that I was less familiar with, without resorting to extended scenes of carnage. There are some brutal and bloody panels in the book but they stop short of depicting the violence, directly, as its happening, instead showing its gruesome aftermath. This is one book I would definitely not recommend for children but those in their late teens or older may get something out of the spine-chilling tale as I did.

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel

Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic is a book that I’ve seen frequently pop up on all-time best graphic novel lists, which in itself makes me interested in checking it out at some point. The name Bechdel is already iconic to me, despite not having read the book yet, due to my awareness of the so-called Bechdel Test for determining if a film or story has a legitimate feminist point of view. Clearly, the author has already had a positive impact on pop culture, so I genuinely want to learn more about her work, in general. Once again being a graphic memoir, Fun Home centers on the author’s troubled relationship with her father, a funeral director, growing up and focuses on LGBTQ+ issues as it relates to her life in unexpected ways. As the story’s synopsis explains, “It was not until college that Alison, who had recently come out as a lesbian, discovered that her father was also gay. A few weeks after this revelation, he was dead, leaving a legacy of mystery for his daughter to resolve.”

Fun Home was the winner of a mountain of accolades, such as being Time Magazine’s #1 book of the year when it came out, in 2006. If that weren’t enough, there’s also a highly-acclaimed musical theater adaptation, which I now badly want to see. Fun Home has also been the focus of bans within the past couple of years, according to CBLDF.

They Called Us Enemy by George Takei, Justin Eisinger, Steven Scott, and Harmony Becker

America’s history of operating internment camps for people of Japanese descent during World War II is one that I don’t know a whole lot about, which is why I’m very interested in reading George Takei’s memoir of his childhood, They Called Us Enemy. Not only would this undoubtedly make an interesting insight into a pop culture icon’s life, but I’m interested to learn about this darker side of American history that often seemingly gets swept under the rug. As the synopsis states, “In 1942, at the order of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, every person of Japanese descent on the west coast was rounded up and shipped to one of ten ‘relocation centers,’ hundreds or thousands of miles from home, where they would be held for years under armed guard.”

I live in Portland, Oregon, so that makes my interest in this book especially relevant since one of these internment camps was located in the city. There are many other connections the Rose City shares with Japan, including a Japanese American Historical Plaza downtown, designed in part to raise awareness about the prison camps, where pink cherry blossoms now bloom each spring. I have a feeling this is going to be one book that I will want to share with some of my middle school-aged loved ones once I read it. according to CBLDF, the book has faced bans in recent years.

Blankets by Craig Thompson

Craig Thompson’s Blankets is another graphic novel that has emerged as one of the most acclaimed of the 21st century. While that alone is reason enough for me to want to check it out, the coming-of-age romance theme against the backdrop of the author’s Evangelical Christian family in a wintry landscape is also an intriguing premise to me, since I had a similar upbringing. The pen and ink illustrations are also beautifully rendered, from what I’ve seen of them, with the cover alone drawing me in like a cozy fireplace. The book also deals with the main character having a crisis of faith, with most who’ve read it recommending the more mature themes for older teens, according to GoodReads. With that in mind, it’s not surprising to hear the book has faced bans as recently as last year, according to CBLDF.