Anna Kendrick makes her debut behind the camera with Woman of the Hour, where she also plays the lead — Cheryl Bradshaw, an aspiring actress trying to make it in Hollywood. Fresh out of luck and out of work, Cheryl feels compelled to accept a reality dating show gig, putting her right on the path of famed serial killer and fellow contestant Rodney Alcala (Daniel Zovatto). This is a true story.

It doesn’t get much crazier, and more ’70s America, than a serial killer joining a campy game show, so Kendrick had plenty of opportunity to fall into a sensationalized trap. Thankfully, Kendrick-the-director’s cool-headedness and empathy shine through every aspect of this production. What could have been yet another true-crime deep dive into the sick mind of a violent man, ended up becoming an unexpected and incredibly welcome look at how societal structures enable those behaviors.

Woman of the Hour never treads uncharted waters in terms of its psychological reflections, or in how it chooses to represent them cinematically, but rather in shifting the perspective from the perpetrator to his victims. The very word “serial” implies a long list of victims, often bundled together and brushed over in these types of stories, but Kendrick makes sure to give each of the women affected by Alcala’s cruelty their space to exist and to leave a mark. There are three stand-out characters, however, each of whom embarks on their respective journey in parallel with the killer.

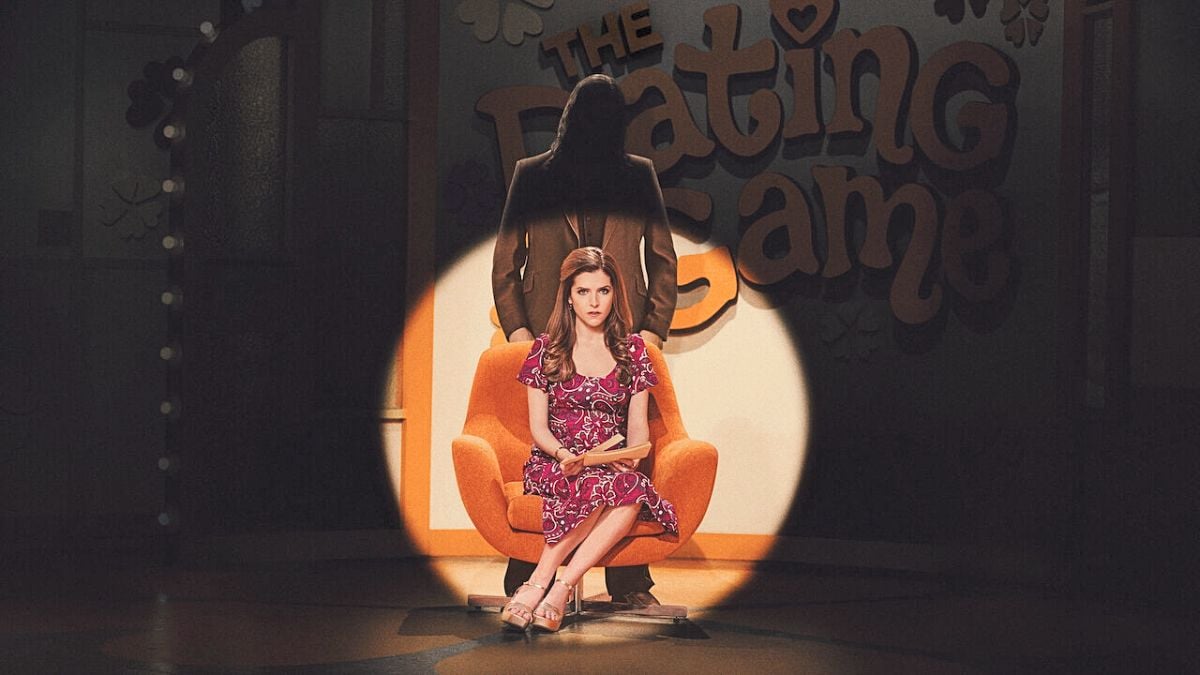

Kendrick’s Cheryl is a compelling protagonist. Fiercely independent and holding on to the very last remnants of her Hollywood dream, she’s easy to root for, and incredibly relatable in the way she fluctuates between making herself small to please others, and standing up for herself in a quest for respect. Women are never only one or the other, only strong or only polite, though the latter is so ingrained in our way of being that it takes a conscious effort to shake off. Woman of the Hour explores this duality in the female characters’ relationships with the men they meet, crystallized especially by the setting and context of The Dating Game (a real game show that began airing on ABC in 1965) and the danger of the serial killer.

The game show host, based on Jim Lange and played by Tony Hale, coaches Cheryl to be polite and unintimidating, and provides her with a set of frivolous questions to ask her far-less-restricted suitors. Their often-racy responses tell her nothing about they would treat her in a relationship, and when she decides to press the men on subjects that actually matter and show her own personality, the whole structure of the show nearly crumbles. The dynamic between the serial killer and his victims, meanwhile, is a constant ping-ponging between playing nice to preserve your life, and not allowing anyone to take advantage of you.

In her film debut, Autumn Best plays Amy, a character based on Monique Hoyt, a young girl who escaped Alcala by sweet-talking him and convincing him she wanted to continue their relationship after he brutally raped her. That’s as clear a statement as any about the place women have been forced to occupy in society in order to survive.

A third vital character in the film is Nicolette Robinson’s Laura, a completely fictional woman who is attending the taping of The Dating Game when she recognizes Rodney as the man who killed her best friend. She tries her best to alert authorities, but is undermined by every man she speaks to about the issue, including her boyfriend, a studio lot security guard, and a police detective. She fails to alert Cheryl before she unwittingly picks the sadist killer as the winner of the game, and agrees to go on a date with him.

As we get to know and learn about these women’s lives, patterns emerge in the way they’re never taken seriously or are seen as expendable, and nearly every man as well as some women in the film are guilty of perpetuating these cycles in one way or another.

On the game show, Cheryl is separated from her suitors by a wall, and only ever gets to hear their voices, judging their character by the answers they give to her questions. It functions as a visual representation of the walls put in place to mask someone’s true nature, and it works — you never really know what someone could be hiding. In the vein of other well-known charismatic killers, Rodney has all the right answers, coming off as an intelligent, enlightened feminist, but when the two finally come face to face on their date, Cheryl is immediately aware of how his face and attitude change whenever she matches his bravado.

Both Kendrick and Zovatto are perfectly cast in their respective roles, and play a key part in grounding Woman of the Hour on the rare occasions its dialogue and staging verge on the theatrical. They’re a great match for one another even if their time together on screen is short. Best’s expressiveness and sense of ease in front of the camera as Amy spell a bright future for the young actress, who steals every scene she’s in.

Woman of the Hour is especially terrifying because of how closely it sticks to very tangible situations and how long it chooses to sit with the women affected, expanding on their emotions and thought processes in a way that will feel unnervingly recognizable to any woman who watches the film. It’s the emotional commitment to the victims and survivors that drives the intensity of its violence, which is remarkably effective at causing discomfort and hurt despite limited explicitness and screen time.

Kendrick makes the most out of Ian McDonald’s screenplay and delivers a very solid true-crime drama that will feel especially chilling, yet simultaneously empowering, for a female audience. It could have been even more ambitious with its storytelling by breaking the molds of serial killer thrillers even more fiercely, as it never strays too far from the typical waves of tension and release that define the genre, but it ultimately succeeds in providing fright, suspense, and the very real pain that comes with misogynistic violence. True crime fans will easily bite into this one, only to discover something truly to chew on on the inside.