Hayao Miyazaki came out of retirement in 2018 to make The Boy and The Heron (whose literal and better translation is How Do You Live? in reference to the 1937 novel of the same name by Genzaburō Yoshino, which plays a part in the film). It’s good that he did because his 12th feature film could not feel more relevant.

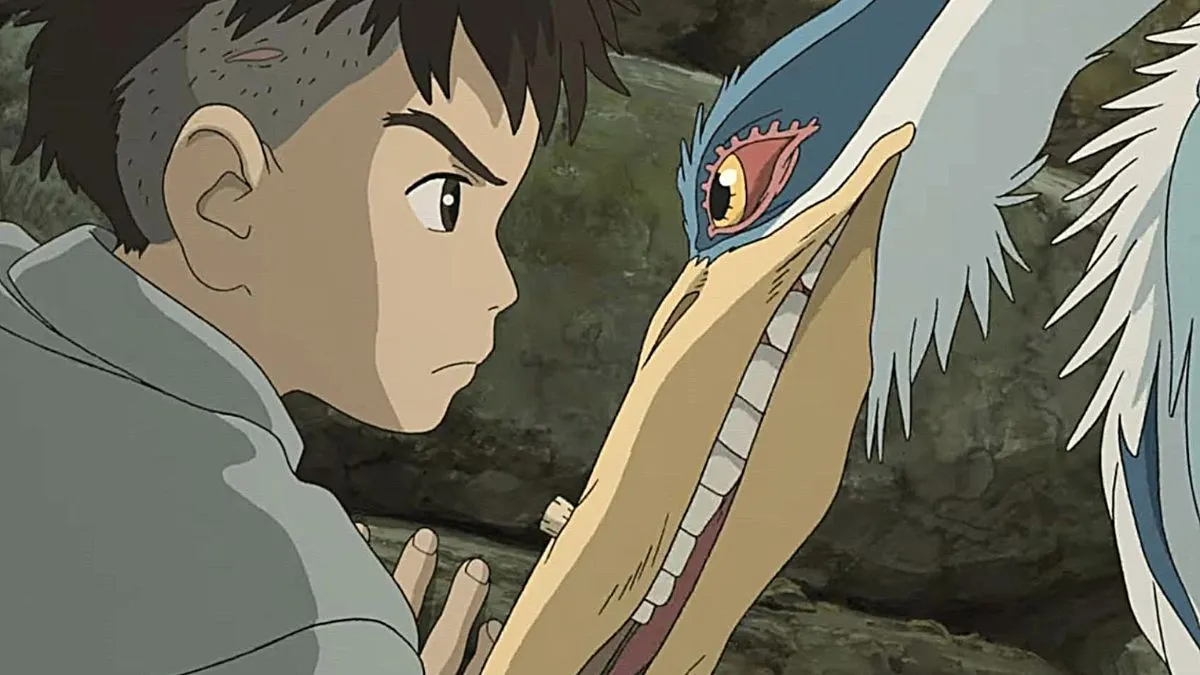

In wartime Japan, Mahito Maki, a 12-year-old boy who lost his mom in a hospital fire, moves to the countryside to live with his new stepmother when an unsettling grey heron starts contacting him with the promise of meeting and reviving his dead mother. Mahito, who is struggling to cope with his grief and all the changes in his life, follows the mysterious animal to a tower in the woods. When his stepmother goes missing in those same woods, Mahito dives into a volatile and epic underworld for an odyssey that will change him forever. What follows is as fantastical as Miyazaki has ever been, combining familiar motifs with what feels like unprecedented boldness in both animation and narrative in the director’s work.

The overarching theme of the genius Japanese filmmaker’s oeuvre has always been the conscientious choice we must make every day to keep our child-like hope alive in the face of horrors and the ugly side of the human experience, or, in other words, the act of growing up and doing it well. Although reducing The Boy and The Heron to this message would be simplistic, given its almost overwhelming density and intricacy, it is also true that it is its most relevant aspect.

There are two equally fundamental sides to this coin. One pertains to the film’s medium, and the other to the world that receives it. In a time when great auteurs are preparing to pass on their legacy to younger generations, the world must contend with the bleakness of the future of filmmaking and storytelling. The Boy and The Heron, through the allegory of a young boy who must save an imaginary world by succeeding his granduncle to the throne, is as much a reminder of the impending death of well-intentioned creativity and the opportunity we all still have to save it.

In a much broader sense, however, Mahito’s journey in Miyazaki’s 2023 film contends with letting go of a fantasy to live in the real world. Being brave enough to see reality for what it is, while maintaining the infinite freedom of creation that only a child’s imagination provides and which will be the ultimate key to keeping the world afloat.

What’s quite frightening about The Boy and The Heron, though, is that just like Miyazaki’s time is running out, so is our innocence. The man behind some of the most enlightening storytelling of the better part of the last 50 years is leaving us with a reality that is shrinking in compassion and reaching a dangerous and uncontrollable state of entropy, much like the end days of the Granduncle’s capsule-like world. Pieces that once held everything together no longer fit, crumbling under the weight of bad choices.

Still, it wouldn’t be a Miyazaki film if it didn’t provide some light among darkness. The director’s faith in the next generations to make the right choices has defined his work and it might just reach its peak in The Boy and The Heron, where he seems to directly address those watching by telling them to never forget the spark that once made them dream. In the same breath, he warns that most people do forget. In its most elementary form, the adventure fantasy epic is a call to action, bravery, and unrelenting hope.

Despite its breathtaking animation, arresting score and sound design, and an adventure of a scale so large it is impossible not to eagerly tag along, The Boy and The Heron also attempts to juggle too many plot points at once, lacking some of the clarity of the director’s previous works. At times, the film does come across as an attempt to incorporate as many concepts as possible, from allusions to other Ghibli films and a brush with the multiverse, to environmentalist admonitions and a surrealist cast of creatures, including a man inside a heron, murderous parakeets, and sylvan organisms called the warawara that eventually become human children. It’s a lot.

The convolution can be distracting and take the viewer away from the film on various occasions, but it is also mostly present in the fantasy world visited by Mahito, which is in a declared state of chaos and disarray, and which he is tasked with saving. Creatures that the Granduncle had brought to this plane evolved in unexpected unpredictable ways beyond their maker’s control. The pelicans, without normal fish to eat, were attacking the warawara, and the parakeets, who had formed their own inner society, were attempting a coup.

As overwhelming as all this information was to receive, it was not gratuitous, complex for the sake of being complex. It was simply a reflection of the inability to control the growing life of your creation after you put it out into the world, much like the main emotional conflict of the protagonist Jiro Horikoshi, the maker of World War II fighter aircraft, in 2013’s The Wind Rises. And a challenge every artist must come to terms with.

The Boy and The Heron is almost like every other major Miyazaki film molded into one and there lies both its geniality and its marring. Nevertheless, it’s easy to foresee its longevity as the years and the trajectory of the remainder of Miyazaki’s career will undeniably shine new light onto young Mahito’s whirlwind expedition through the land of dreams, imagination, and childhood.

Fantastic

Hayao Miyazaki's 12th and possibly final feature film could not be more relevant as a call to action, bravery, and the unrelenting hope of childhood.

The Boy and The Heron