When 73 British, American, and Scandinavian children boarded a steamboat in Shanghai on January 29, 1935, little they did they know that they would soon be fated to meet a notorious band of pirates who had harassed the Chinese coast for decades.

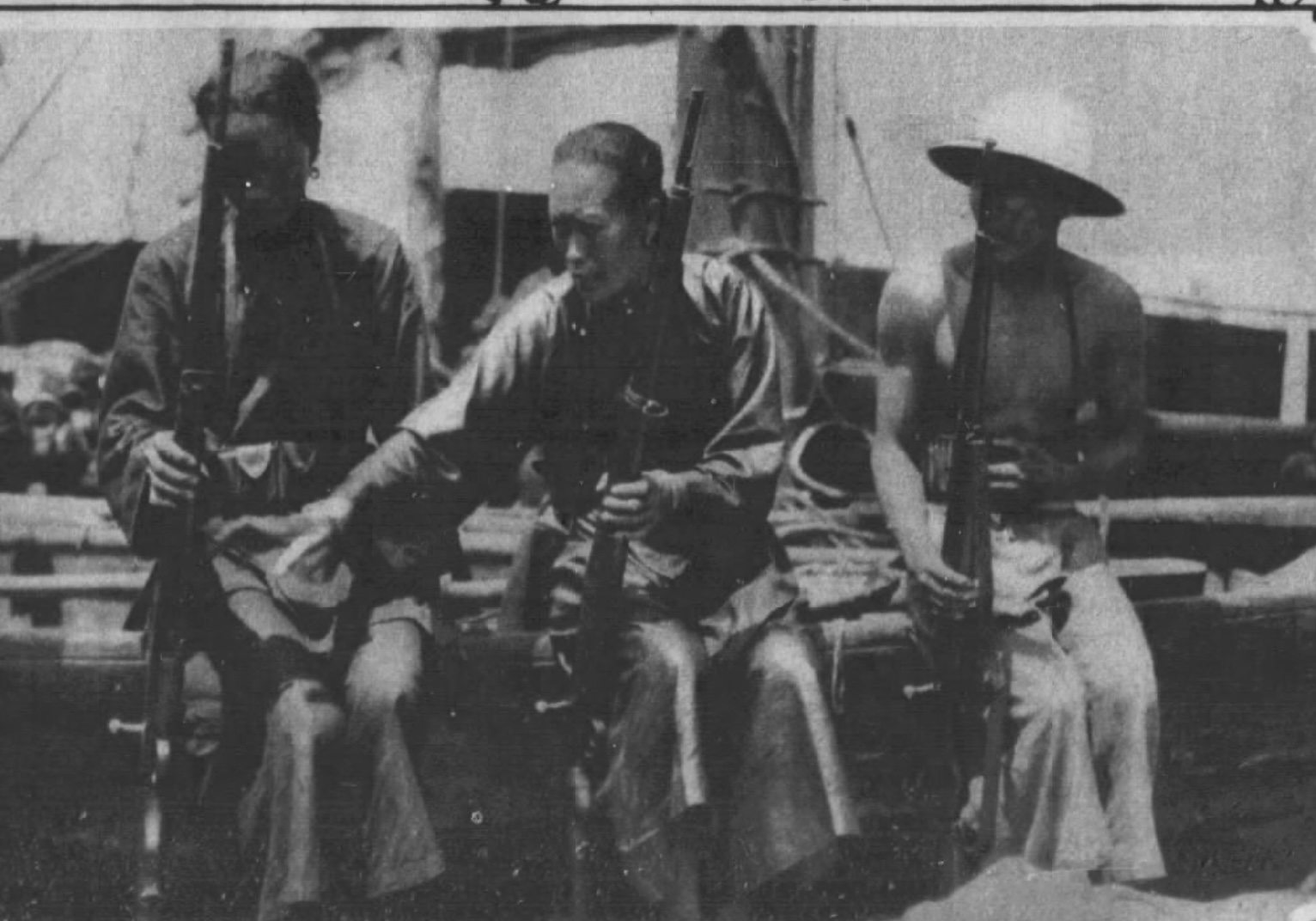

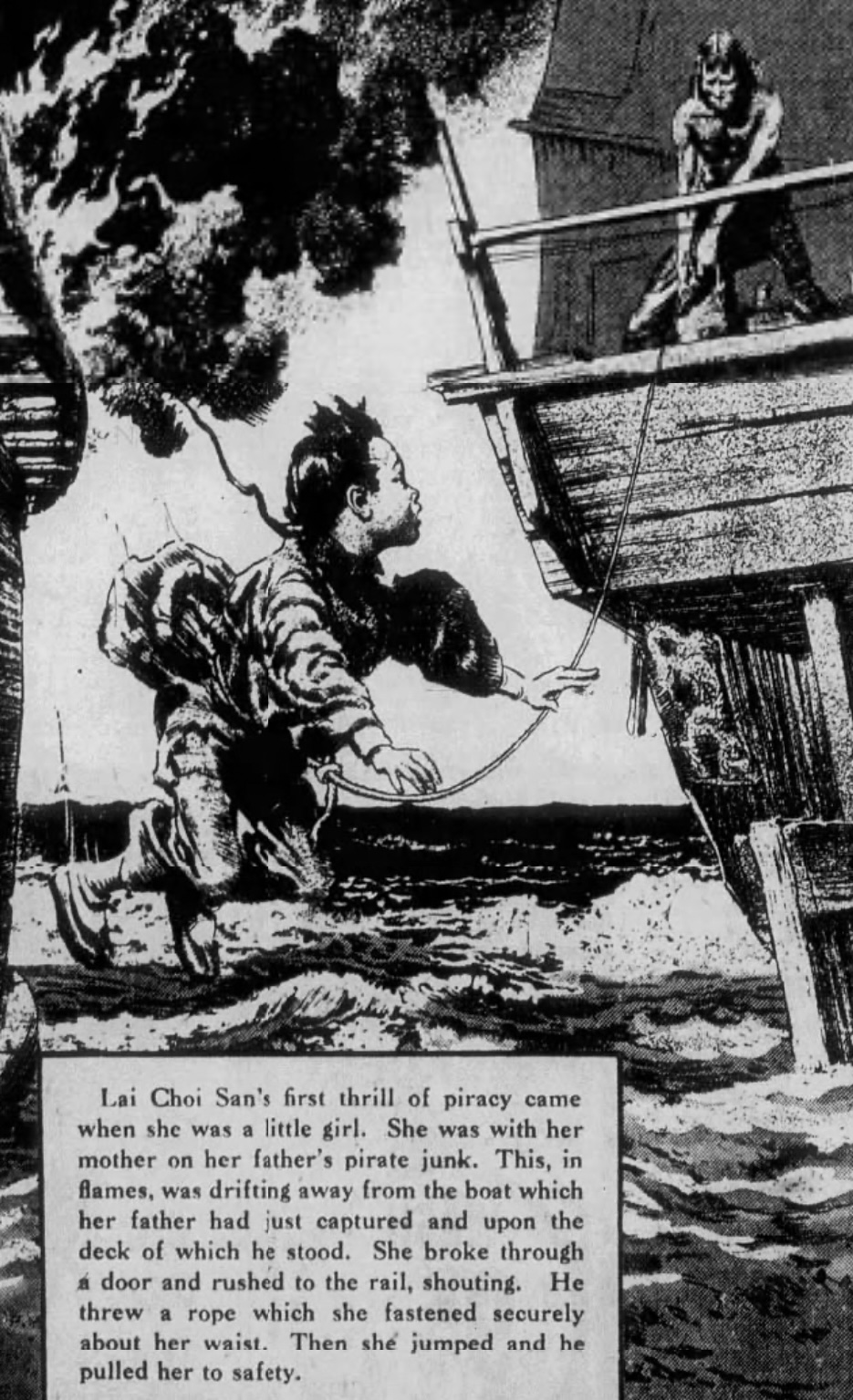

One of the last significant pirate strongholds, Bias Bay lies in the southern coast of Guangdong province in southern China, not too far from Hong Kong. The Bias Bay pirates were led by the female pirate Lai Choi San, who is believed to have had thousands of Chinese junk ships at her command. One such ship would cause global attention.

The Pirates Attack

When the steamboat known as the SS Tungchow embarked from Shanghai, it was expected to dock in Yantai within a day, where most of its passengers — 73 kids of various ages — would be studying at the Chinese Inland’s Missions School, also known as the Chefoo School, whose purpose was to provide an education for the children of foreign missionaries and businessmen. Most of those foreign families lived in Shanghai, so this was a return trip for the children after visiting their respective families.

At 6pm on that Tuesday night of January 29, shortly after the passengers had finished their dinner, a lone, unthreatening junk ship appeared nearby, but a commotion on deck earned the attention of the guards; a shot rang out as several passengers of the Tungchow suddenly drew firearms and started barking orders. These gun-wielding assailants were pirates, and had boarded the ship in Shanghai alongside other passengers. As they made their move, the junk ship came closer and rode alongside the steamboat uncontested, its hidden cannons not required.

Overall, only 13 pirates total boarded the Tungchow, but that’s all the manpower they needed.

Mr. K. Macdonald, the second engineer for the steamboat, immediately rushed out of his cabin upon hearing the alarm. He was met by the pirates, and gunfire ensued. Shot in the chest, Macdonald nevertheless somehow lived to tell the tale of the attack.

Two of the four Russian guards of the ship were also shot, including one who had fought against four of the pirates. Multiple accounts claim he was still alive some 20 minutes later, but was then brutally killed. The other guard who was shot survived. The other two guards were overwhelmed and taken captive by the pirates along with the other passengers, including the children. The captives were then held in the ship’s saloon.

Fool’s Gold

The pirates had acted so swiftly that they had already taken the radio operator hostage, preventing any word from getting out. They had quickly taken the captain hostage also, and stormed the engine room.

One uncredited account detailed what happened next, which reveals what the pirates were after:

“Ordered to unlock the door of the strong-room, the purser did so without the slightest reluctance, but so eager were the pirates to see the gold that they delayed him by trying to speed him up with nudgings of their guns. Finally the heavy, burglar-proof steel door swung open, with a dismal groan which was echoed by even more dismal ones from the pirates when they saw that it contained nothing, not even a speck of dust.”

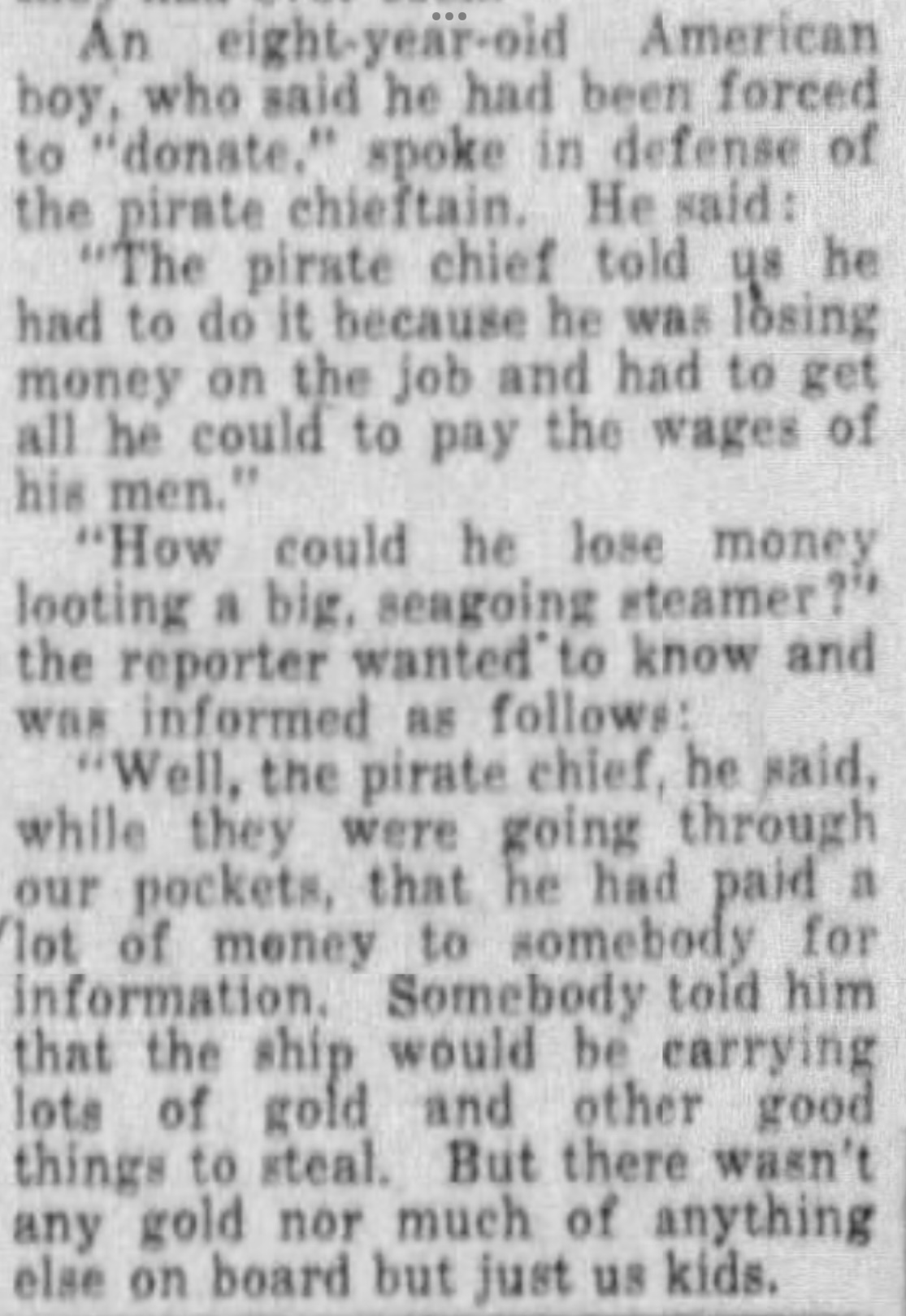

The pirates, furiously disappointed upon realizing they had been lied to, needed to decide what to do next. They could leave with only the money they took from each passenger, as well as some random loot from the ship — or they could take hostages. They decided to steer the ship south towards Bias Bay, which was a couple days away. With 73 children held captive, surely a significant ransom would be paid. Thus, they departed the Yellow Sea and headed for the South China Sea.

Once in Bias Bay, they would be safe from the authorities and in their own den of pirates, including the ruthless Lai Choi San herself.

The Tungchow Disappears

When the ship was nearly a day late to arrive at its destination of Yantai, the port informed authorities.

All ships were then on the lookout for the Tungchow, but two days passed without a single sighting, despite the Chinese and British governments reacting by sending out ships in a desperate search for the steamboat, while also informing others in the waters. The British and the Chinese assumed there was a chance that if the Tungchow had been taken over by pirates, then it would be headed to Bias Bay, but even along that sea route, there was no sign of the Tungchow. It was as if the ship had completely disappeared. Did it sink? Did it vanish?

As it turns out, the pirates did make the Tungchow disappear. No, it wasn’t magic.

Once the pirates decided to stay on the ship and head to Bias Bay, they employed a clever plan; they painted the ship’s funnel red, and also painted over the name “SS Tungchow.” They even repainted a new name, “Toa Maru,” onto the ship.

Hence, the Tungchow sailed through busy waters unspotted. It even passed numerous ships that were looking for it, including within close range of a searching British vessel; the pirates succeeded in completely disguising the ship. It no longer fit the description of the Tungchow, and did not bear its name. The Toa Maru was not just a random name, either; it was the name of a known ship, one that had been recently restored near Hong Kong.

The Pirate Chief And The Children

As the 13 pirates, led by an unnamed chief, controlled the ship and its passengers, they at least made sure everyone was fed. When one adult passenger, described as “a pompous man with a large mustache,” complained that he didn’t have enough to eat, the pirates would poke him with their guns. The man also behaved miserably towards the children, saying he believed they should all keep quiet. The pirate chief noticed that the children were rather delighted at seeing the pirates trouble the man, so he made sure to nudge him whenever he spoke as a way to keep him quiet, instead.

Mr. PJ Duncan, the master in charge of the 73 children — and whose detailed account was cited in newspapers around the world in the following months — pointed out the unique relationship that formed between the chief and the children.

The pirate chief took a liking to the youngsters, because instead of being afraid of him, they were in awe. They had never seen a real life pirate before, and their adventurous spirits were too star-struck to understand the gravity of the situation. Despite the pirates having shot three men, killing one, the children were admiring observers of a real-life pirate movie unfolding before their eyes.

The pirate chief would often grab oranges stored on the ship, and toss them to the children only. He even found candy stored on the ship, and give the children treats. He entertained them with his pirate stories, and his rather unusual upbringing of being raised by a pirate to be a pirate, which many in Bias Bay were. It’s likely that this pirate chief — only described as “fairly young” by Duncan — never met such a delighted audience for his tales outside of Bias Bay.

The British Navy Near Bias Bay

A month earlier, a British carrier named Hermes had stationed itself in Hong Kong. When authorities were notified of the missing steamboat with many British children aboard, the British navy quickly reacted, and Hermes was immediately dispatched.

At noon on Friday, February 1, aircraft from the Hermes spotted a steamboat just outside Bias Bay, seemingly headed towards a location known to be a pirate den. The pilots realized it could be the Tungchow in disguise, and they were right.

The pirates, upon realizing they’d been spotted, quickly hopped onto a lifeboat with two adult hostages in order to prevent the aircraft from firing. They had made off with some loot from the steamboat, also. They weren’t alerted of any aircraft search ahead of time because they had, regrettably, destroyed the Tungchow’s communications. The pirates then headed for a small island nearby. Upon reaching shore, they left the hostages there. Once the surveilling aircraft departed, the pirates sailed away to a larger boat of their own, and raced safely to Bias Bay before more help arrived to take the Tungchow home.

The only life lost in the affair was that of the Russian guard, whose name was only published as “Tchornoff.” All other passengers survived. None of the 73 children were harmed.

The Pirate Chief Bids Farewell To The Children

When the pirate chief initially departed the Tungchow on the lifeboat, he turned around to face the children, all 73 of whom were looking at him. He flamboyantly bowed towards them, as a theater actor might after giving a performance worthy of a standing ovation. As the lifeboat reached closer to the shore, he turned around again to offer another bow, but the children had all dashed to the other side of the Tungchow in an attempt to grab the pirate chief’s sweater, which he had unintentionally left on board. In doing so, they accidentally ripped it to pieces, and thus many kept a small piece to themselves.

Spared were the children from meeting the leader of all pirates, Lai Choi San.

Was the pirate chief really going to keep the children hostages in Bias Bay? One account claims that the pirates had already boarded a lifeboat and had began heading to the small island before any aircraft were spotted. If true, then why leave the children there? Did the children’s admiration for the pirate make him have a change of heart? One can only assume or, perhaps more accurately, believe that the tale deserves such an ending.

During the ordeal, and most especially afterwards, newspapers around the globe reported the occurrence. This article was pieced together by reading all known accounts of the incident, including detailed reports in the San Francisco Examiner, The Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, and the Liverpool Daily Post, amongst many other newspapers.

Published: Mar 1, 2024 02:33 pm