In Dec. 2023, Alabama was prepared to execute convicted murderer Kenneth Smith using inert gas asphyxiation, an untried method of capital punishment only approved in three U.S. states — here’s how inert gas asphyxiation works and why this untested form of capital punishment is controversial.

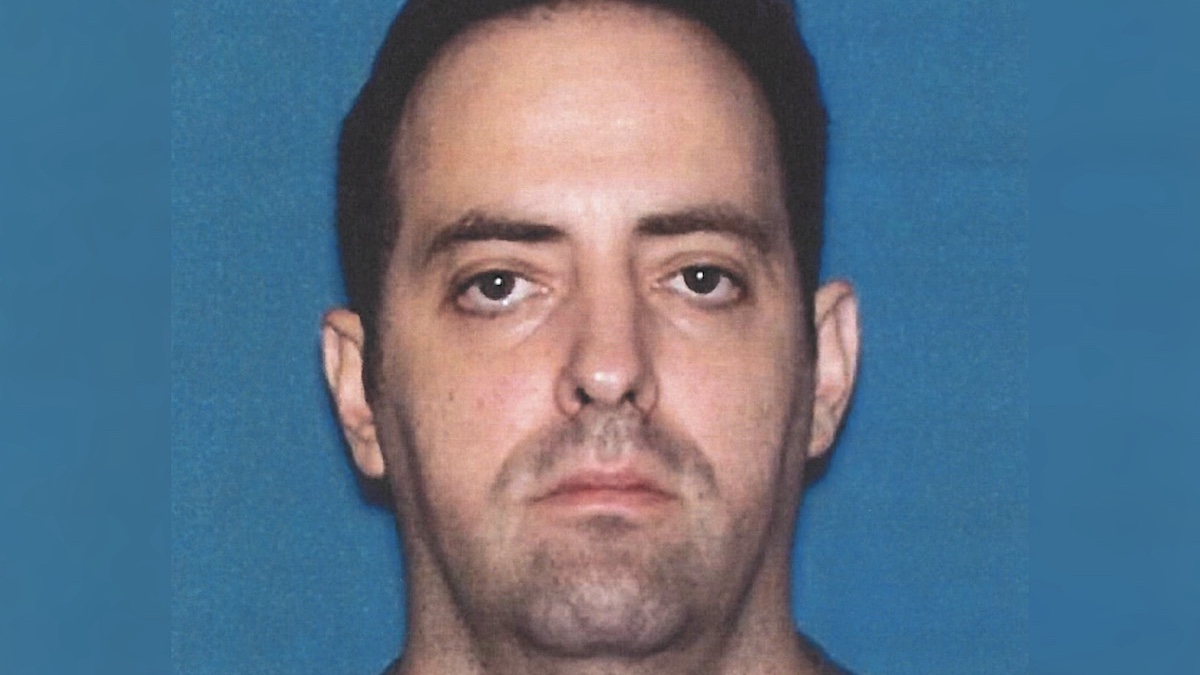

In 1988, Smith was one of two men convicted of killing Elizabeth Sennett in a true-crime, murder-for-hire plot staged to look like a home invasion. Sennett’s husband, Charles Sennett, a pastor in Alabama, reportedly hired the men to kill his wife over an alleged affair and financial problems. Charles died by suicide before charges were brought against him, AL.com reported. Smith confessed to his role in the crime.

What is inert gas asphyxiation?

Inert gas asphyxiation, sometimes called nitrogen hypoxia, kills by replacing someone’s oxygen supply with nitrous gas via a mask until the person supposedly falls asleep and effectively suffocates. Some say inert gas asphyxiation is a more humane and painless way for someone to die compared to other methods of capital punishment. According to those who oppose inert gas asphyxiation, however, the approach is too experimental to be sanctioned by the state, according to NPR.

The gas used in the inert gas asphyxiation could also pose a threat to witnesses and religious leaders who typically attend state executions, potentially violating the prisoner’s religious liberty, opponents add.

Questions remain about Kenneth Smith’s execution protocol

In advance of Kenneth Smith’s planned execution via inert gas asphyxiation, the state of Alabama released a heavily redacted protocol explaining how it would be carried out concerning Fordham Law School death penalty expert Deborah Denno. “This is a vague, sloppy, dangerous, and unjustifiably deficient protocol made all the more incomprehensible by heavy redaction in the most important places,” Denmo told the AP.

According to former Alabama state senator Trip Pittman, who supports the method, “[nitrogen gas] is readily available. It’s 78% of the air we breathe, and [inert gas asphyxiation] will be a lot more humane to carry out a death sentence” (via AP).

As of Kenneth Smith’s planned execution in Jan. 2024, inert gas asphyxiation was only approved in two other U.S. states beyond Alabama: Mississippi and Oklahoma. At first, Smith requested inert gas asphyxiation before his failed lethal injection, but that request was denied.

At the time of this writing, Smith’s planned execution would be the second attempt in Alabama to carry out the sentence. In 2022, his execution by lethal injection was aborted because a vein could not be located, according to the AP. John Forrest Parker, the other man convicted for Elizabeth’s death, was executed by lethal injection in Alabama in 2010.

Published: Dec 13, 2023 03:20 pm