On Nov. 11, 1988, authorities discovered a dead body buried in the ground while inspecting the house of Dorothea Puente at 1426 F Street in Sacramento, California. Six more bodies would be unearthed later. Puente, who was 59 years old at that time, ran a boarding house for the elderly and those who suffered from mental illness.

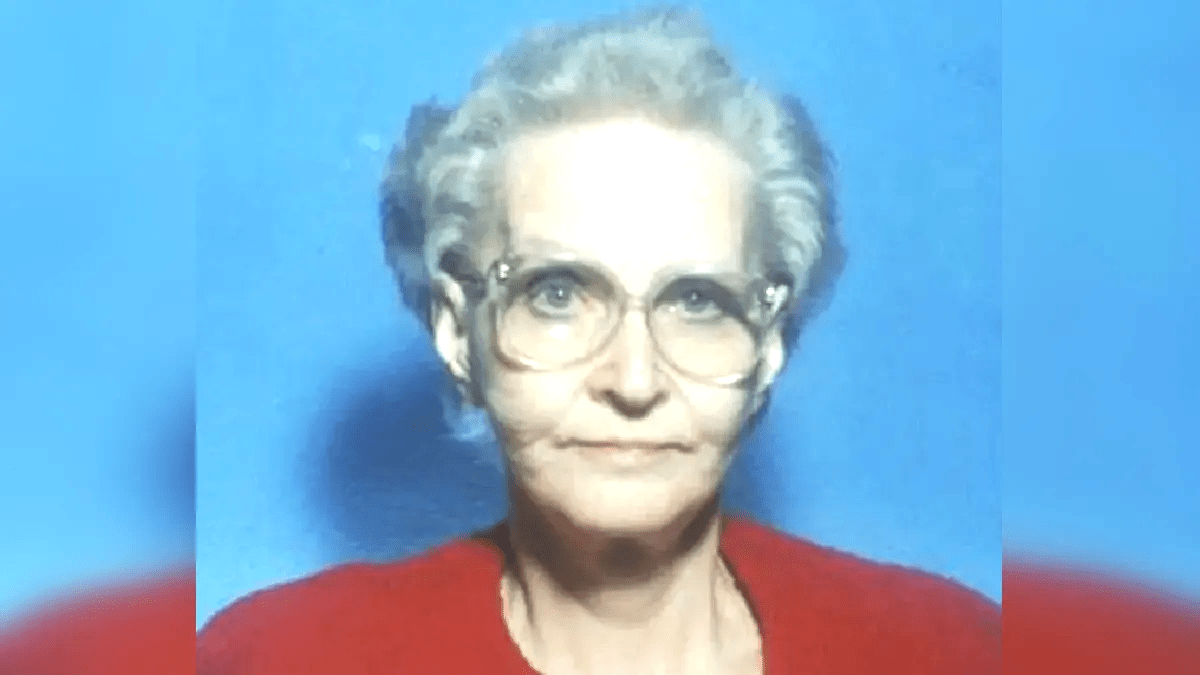

Anyone who saw Puente – who looked like your average grandma with thick glasses and short gray hair – wouldn’t think she was a serial killer. Little did those around her know that she was a vicious murderer who preyed on her vulnerable tenants.

Dorothea Puente’s background

Dorothea Helen Gray was born in California in 1929, and from an early age, life was difficult. Her father died from tuberculosis when she was just 8 years old and her mother died in an accident a year later. The circumstances forced her to live in an orphanage, and in her teen years, she dabbled in prostitution.

Dorothea married at 16, though her marriage certificate listed her identity as 30-year-old Sherriale A. Riscile. She had two children with her husband, Fred McFaul, but one was put up for adoption, while the other was sent to live with relatives. A third pregnancy resulted in a miscarriage. By that time, she started forging checks, and her husband divorced her after her arrest.

She married Axel Bren Johansson in 1952, this time under the name Teya Neyaarda. Her new husband, a seaman, spent the majority of his time away from home, and Dorothea gambled his earnings. In 1960, she was arrested for running a brothel, and the following year, Johansson had her admitted to a hospital after a series of unstable behaviors. There, she was diagnosed as a pathological liar. Dorothea’s second marriage came to an end in 1966, and she then changed her identity to Sharon Johansson.

Her third marriage was to Roberto Jose Puente in 1968, but just like her previous marriages, the union didn’t last, but she kept his last name. Dorothea’s fourth marriage to a man named Pedro Montalvo happened in 1976. The marriage lasted just a week due to Dorothea’s absurd spending habits. Throughout those decades, Dorothea continued forging checks and using different identities to evade detection.

Dorothea Puente continued her scam

In the 1970s, Puente focused her attention on her boarding house. She wore clothing that made her appear older than her age, and she let her gray hair grow out. Those who knew her saw a Christian woman who loved giving back to her community by welcoming those who struggled into her boarding house. She opened her doors to the homeless, those who had substance abuse issues, the mentally disabled, and senior citizens who had no one to care for them. On the outside, Puente was an old lady who cared for the welfare of the individuals she took in, but in reality, she had nefarious reasons for doing so. In 1982, however, she was sent to prison for three years after being caught for cashing in her tenants’ benefit checks and drugging and stealing from an individual.

Puente opened her second boarding house on F Street after her stint in prison. She targeted those who had no close family or friends who would go looking for them if they went missing. There were disappearances, mysterious deaths, and stolen money and jewelry, but it wouldn’t be until 1988 that authorities became suspicious that Puente was a killer.

How was she caught?

In 1988, social worker Judy Moise became concerned for Alvaro “Bert” Montoya, a 52-year-old man whom she had put under the care of Puente in her boarding house. Montoya was a large man but had a gentle nature. He suffered from psychosis and had spent years in shelters or on the streets. Moise made it a point to check up on Montoya, but at one point, Puente told her that he no longer lived in her boarding house. Moise asked the old lady where Montoya went, to which she answered he had gone to Mexico with his brother. This was highly suspicious to Moise as she knew the man had no contact with his family, and she went to the authorities to file a missing person report.

Authorities checked Puente’s house and questioned her and another tenant, and both said the same thing — Montoya left and was no longer living there. However, before the authorities left, the tenant slipped a piece of paper in one of the officer’s hands. The note read, “She’s making me lie for her.”

The police returned to Puente’s house to make a more thorough search. They asked Puente if they could dig in her backyard, to which she agreed. One of the policemen found cloth, eggshells, and beef jerky, which they later found out to be human flesh. Puente was questioned but denied knowing anything about it.

Investigators returned the following day, and while they were digging, the old lady said she was going out to meet a family member for coffee. Since she wasn’t under arrest, she was permitted to leave the premises. Unbeknownst to the investigators, Puente planned to run away, as she knew it was only a matter of time before they unearthed more bodies. She fled to Los Angeles while officers were busy at her home. In total, six more bodies were unearthed in Puente’s backyard that day, one of whom was later identified as Montoya.

Dorothea Puente’s modus operandi

After a few days on the run, Puente was captured and returned back to Sacramento. She was charged with nine counts of murder. Throughout the investigation, it became clear that Puente lived the majority of her life deceiving people and stealing from them, but her illicit activities escalated to murder when she started operating her boarding house. She created a grandmotherly persona and built a reputation that would allow people to trust her. According to the prosecution, Puente killed her tenants with drugs, buried them in her backyard, and cashed their disability or social security checks.

Throughout her interrogation, Puente never wavered and insisted she didn’t kill her tenants. William Vicary, a forensic psychiatrist, assessed Puente before the trial and said she was smart and pleasant, but as the trial drew near, she became paranoid and flustered. She was diagnosed as suffering from antisocial personality disorder or sociopathy. Some of the symptoms include a lack of remorse, disregard for right or wrong, using charm to manipulate others, and telling lies.

Puente’s trial lasted for five months. One of the jurors said that she sat emotionless through the proceedings. “It’s like she was watching a movie she wasn’t particularly interested in,” the juror said. In the end, Puente was convicted on one count of second-degree murder and two counts of first-degree murder. The other six ended up with a hung jury. She was sentenced to life in prison without parole, and she died of natural causes in 2011 at 82 years old.