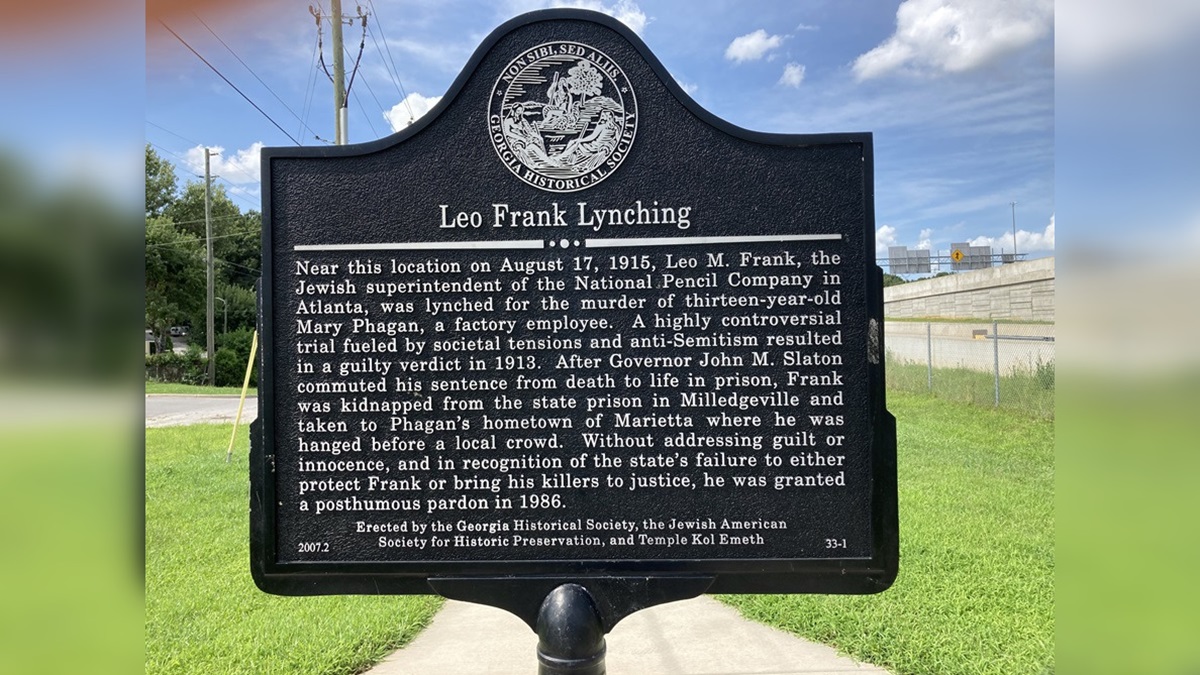

In the early 1900s, Atlanta, Georgia, was a hotbed of anti-Semitic and racial tensions. It was further fueled by the lynching of Leo Frank, a Jewish factory superintendent who was accused of murdering a 13-year-old girl named Mary Phagan.

Jewish immigrants had settled in Atlanta just a few years after the capital’s founding in 1837. There, the small Jewish community thrived by setting up businesses, which attracted more Jewish newcomers. By 1910, Atlanta had about 4,000 Jewish residents, which was roughly 2.6 percent of the population. They were ostracized for cultural and religious differences, and many harbored resentment toward them for having successful businesses.

Who was Leo Frank?

Leo Frank was born in Texas in 1884, and raised in Brooklyn New York. He earned a mechanical engineering degree from Cornell University in 1906, and after spending time in Germany for his apprenticeship, he settled down in Atlanta in 1908, where he worked as a superintendent at the National Pencil Company, a business that his uncle partly owned.

In 1910, Leo married Lucille Selig, who came from a distinguished Jewish family. By all accounts, the couple had a good relationship. Lucille described Leo as a good husband and said, “I have the right to love him very much indeed and I do. If I make too much of him, perhaps it is because he has made too much of me.” Two years after their marriage, Leo became the president of the Atlanta B’nai B’rith, a Jewish organization that assisted Jewish members of the community.

The murder of Mary Phagan

Mary Phagan, who was originally from Marietta, Georgia, started working at just 10 years old to help support her family. The Phagans moved to Atlanta in 1912, and she gained employment at the National Pencil Company, where she operated a machine that attached erasers to the ends of the pencils. April 26, 1913, was a Saturday and the factory was closed, but Mary planned to drop by and get her final pay, as she had been laid off just days prior. Leo was there to hand out wages, as well as work on reports in his office.

Mary didn’t return home that night, and on April 27, just a few hours after midnight, the factory’s watchman, an African American man named Newt Lee, discovered the body of Mary in the factory’s cellar. He alerted the police, and the investigation started.

Based on the autopsy conducted by Dr. H.F. Harris, Mary suffered a blow to the head, which wasn’t fatal but could have knocked her unconscious. She also had bruising on her face, and there were signs of violent sexual assault. Based on her last meal and stomach contents, the doctor concluded that Mary was killed some time between 12:00nn to 12:15pm on April 26. Her cause of death was strangulation.

The investigation

Close to Mary’s body was a sliding door that opened into an alleyway. It was tampered with, and bloody fingerprints were present. Beside Mary’s body were two notes that initially appeared to be written by her. However, upon further examination, they were determined to have been written by the perpetrator to divert suspicion. The lingo and handwriting were not a match for Mary. Based on bloodstains, it was also determined that Mary was attacked on the second floor of the building where Leo’s office was located before the body was transported down to the cellar.

Lee, who was the one who discovered Mary’s body, was arrested and questioned as one of the notes implicated that a Black man committed the crime, but he was later released when it was determined that he had nothing to do with Mary’s death other than being the one who discovered her lifeless body. Authorities also questioned Leo, who said the last time he saw Mary was shortly after noon on April 26 when she got her pay. He told them he was working in his office and left at about 6pm. He voluntarily showed his body to authorities, and no cuts or bruises were found.

Another person of interest was Jim Conley, an African American who worked as a janitor in the factory. A watchman told authorities that he saw Conley washing blood out of a shirt, which was later determined to be rust. Conley also had criminal records resulting from public intoxication. When questioned, Conley said he could neither read nor write, but his statement was later determined to be a lie. After further interrogation, the janitor admitted he had written the notes found near Mary’s body, but claimed that Leo told him to do it. Conley changed his story several times, and in the end, he said Leo killed Mary, transported her body to the cellar via the elevator, and asked him to write the two notes.

In May, an indictment was requested against Leo. There was no indictment against Conley, whom the prosecution called to testify as the main witness against the factory superintendent.

The trial of Leo Frank

Leo Frank’s trial began in late July, and the courtroom was packed. Conley claimed in his testimony that Leo alerted him that a girl was stopping by, and to listen when he stomped his foot, a signal to lock the door. He said he heard a girl scream and when he headed to Leo’s office, he saw him holding a rope. The superintendent allegedly told him, “I wanted to be with the little girl, and she refused me, and I struck her and I guess I struck her too hard…” Afterward, Leo allegedly offered him money to help dispose of Mary’s body.

The defense presented Leo’s activities on the day of the murder to show that he didn’t have the time and opportunity to commit the crime. Several witnesses testified about Leo’s character and good standing in the community, though there were others who said Conley was a known liar. The superintendent also testified in his own defense, reiterating what he told investigators: the only interaction she had with Mary was when he handed her her salary, after which she immediately left his office. He said Conley’s statements and the women who came forward to accuse him of sexual advances all lied. “I have told you the truth, the whole truth,” Leo declared.

The evidence against the defendant was circumstantial at best, and the prosecution’s star witness changed his story several times throughout the investigation, yet the jury found Leo Frank guilty, and he was sentenced to hang. Crowds outside the courthouse repeatedly chanted, “Hang the Jew!”

The lynching of Leo Frank

In the years following, Leo’s lawyers filed multiple appeals to the Georgia Supreme Court as well as the U.S. Supreme Court, but they were all denied. His lawyers turned to Georgia Governor John Slaton for a pardon, and Slaton reviewed thousands of documents. He also received information from the judge who presided over Leo’s trial that he wasn’t convinced Leo was guilty. In addition, Conley’s lawyer wrote the governor to say he thinks his client was guilty of the crime, not Leo Frank. Slaton commuted Leo’s sentence to life in prison in hopes that he would eventually be released when the truth came out.

Leo was transferred to a Milledgeville prison farm. On the night of April 16, 1915, a 25-person group who called themselves the Knights of Mary Phagan broke Leo from his cell, drove him for hours to Mary’s hometown of Marietta, and hanged him from an oak tree at 7AM on the morning of April 17.

Later developments

In 1982, 83-year-old Alonzo Mann revealed a bombshell. At the time of the trial, he was a 14-year-old office boy at the factory. In his 1983 confession, Mann told The Tennessean that Conley murdered Mary. Mann claimed he saw Conley carrying Mary’s limp body on the day of her murder, and that the janitor had threatened to kill Mann if he told anybody what he saw. The frightened boy told his mother about it, but was told to keep the information to himself, and not to get involved. Mann was subjected a a psychological stress evaluation as well as a lie detector test, which he both passed. He said he wished he revealed what he knew at that time, but he was scared and didn’t think Leo would be convicted.

In 1986, the state of Georgia granted Leo a posthumous pardon. The Atlanta Jewish Federation, American Jewish Committee, and the Anti-Defamation League submitted a petition that read the state was not being asked to prove that Leo was innocent, but rather that the state failed to protect him. The Board of Pardons and Paroles granted the request, and recognized its failure to safeguard Leo, and to bring his killers to justice.

Published: Aug 26, 2024 01:57 pm