Neil Gaiman’s beloved The Sandman comic series is having a moment in the sun. Since the first issue hit shelves in January 1989, comics fans have known The Sandman was something special, with the years following seeing the fandom grow as more and more people picked up the collected editions. But, with the critically acclaimed Netflix show having just premiered, the story of the Endless is now being enjoyed by millions of people around the world.

But though The Sandman has encompassed comics, audiobooks, TV shows, and various spinoffs, it’s never ventured into the world of video games. That’s not to say there haven’t been attempts, with WadjetEyeGames’ Dave Gilbert revealing in 2015 that he’d pitched a concept and test image:

But nothing ever came of it and there has never been a game based on The Sandman. Or has there?

The Sandman: Love and Magic

In 1984, Amstrad released the 8-bit Color Personal Computer (CPC), which was popular in European markets as an alternative to the Sinclair Spectrum and Commodore 64. By 1995, the thing was practically obsolete, with console gamers already getting to grips with the Sony PlayStation and PC players gearing up for iD Software’s groundbreaking Quake.

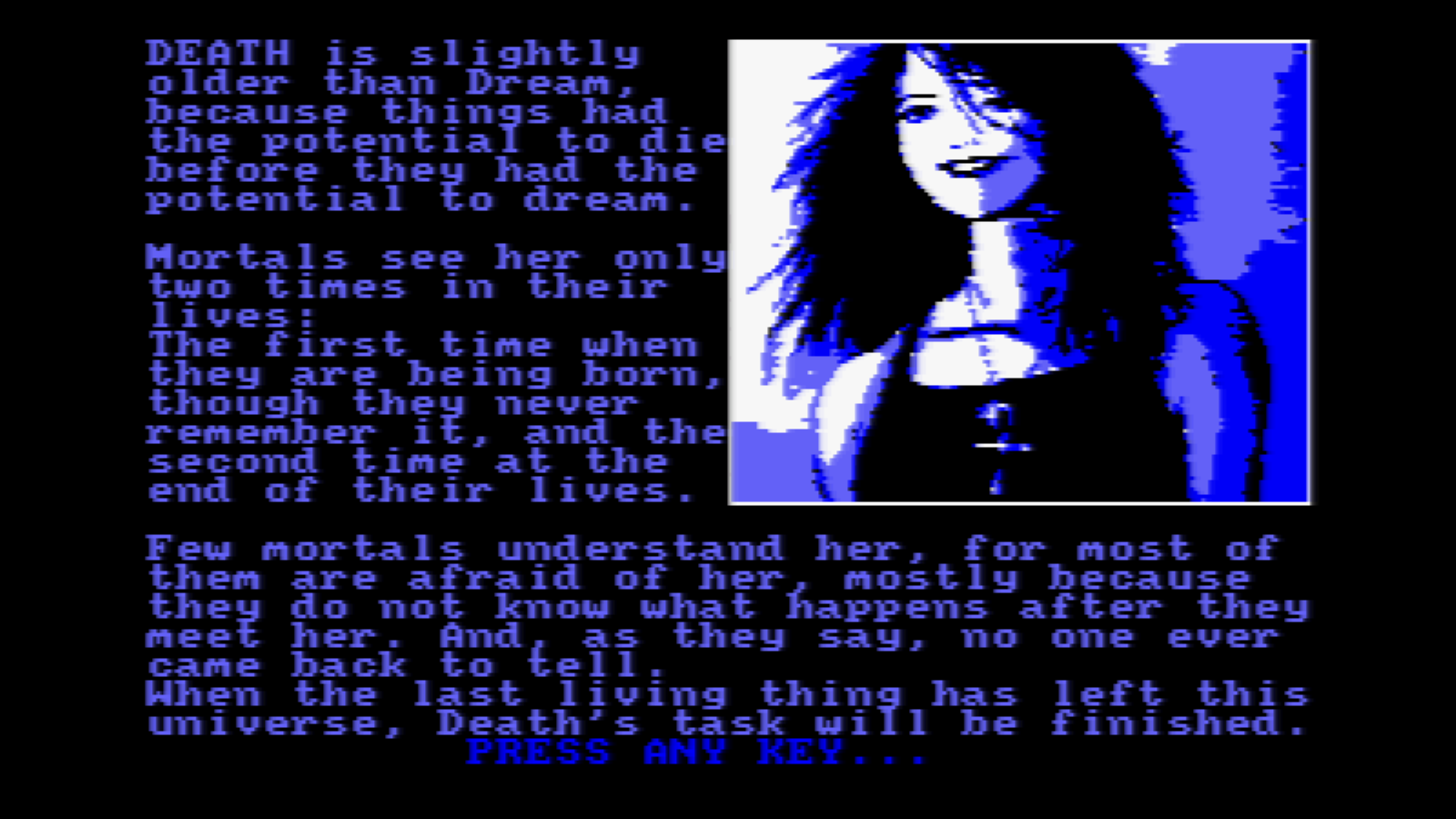

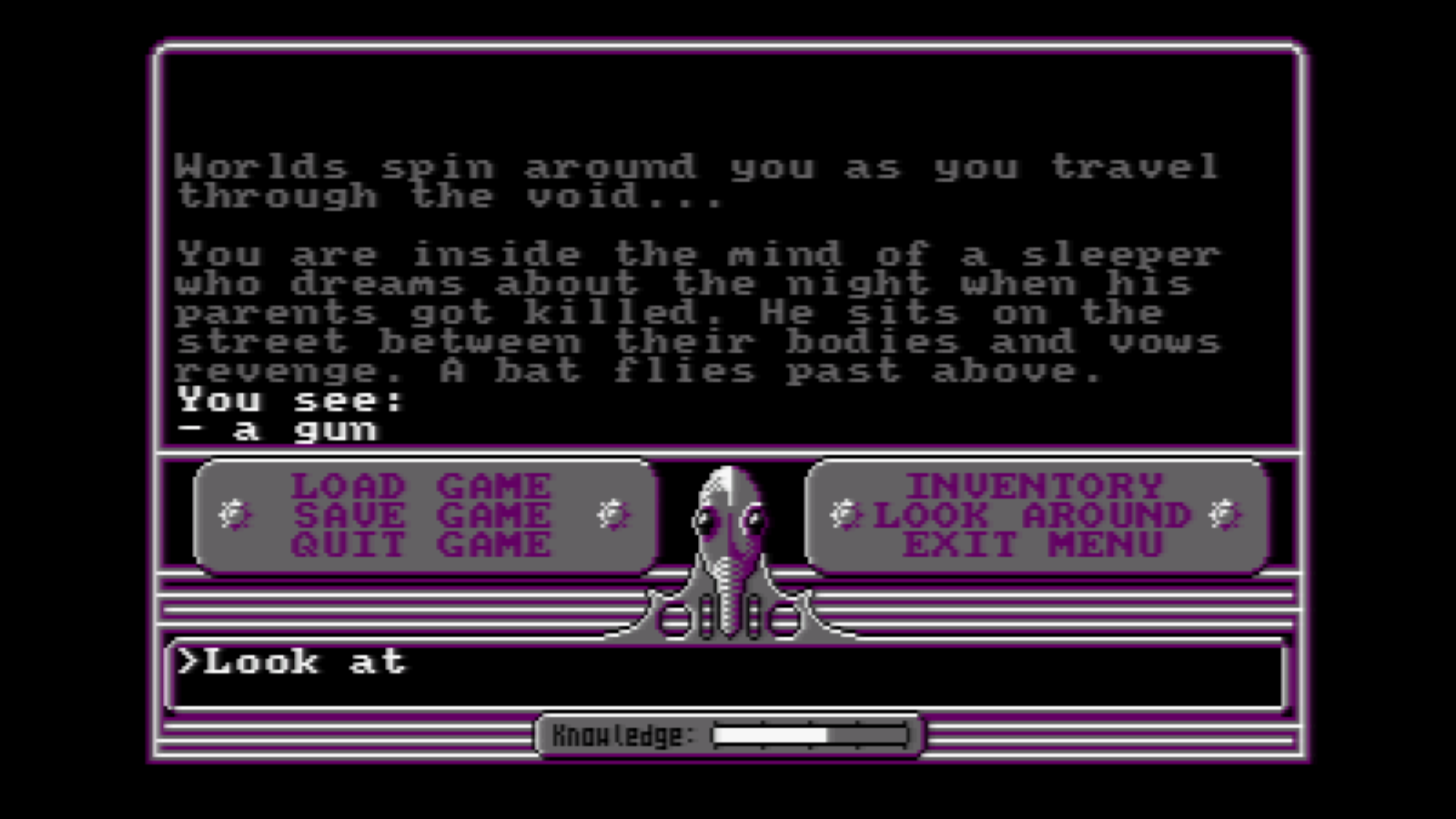

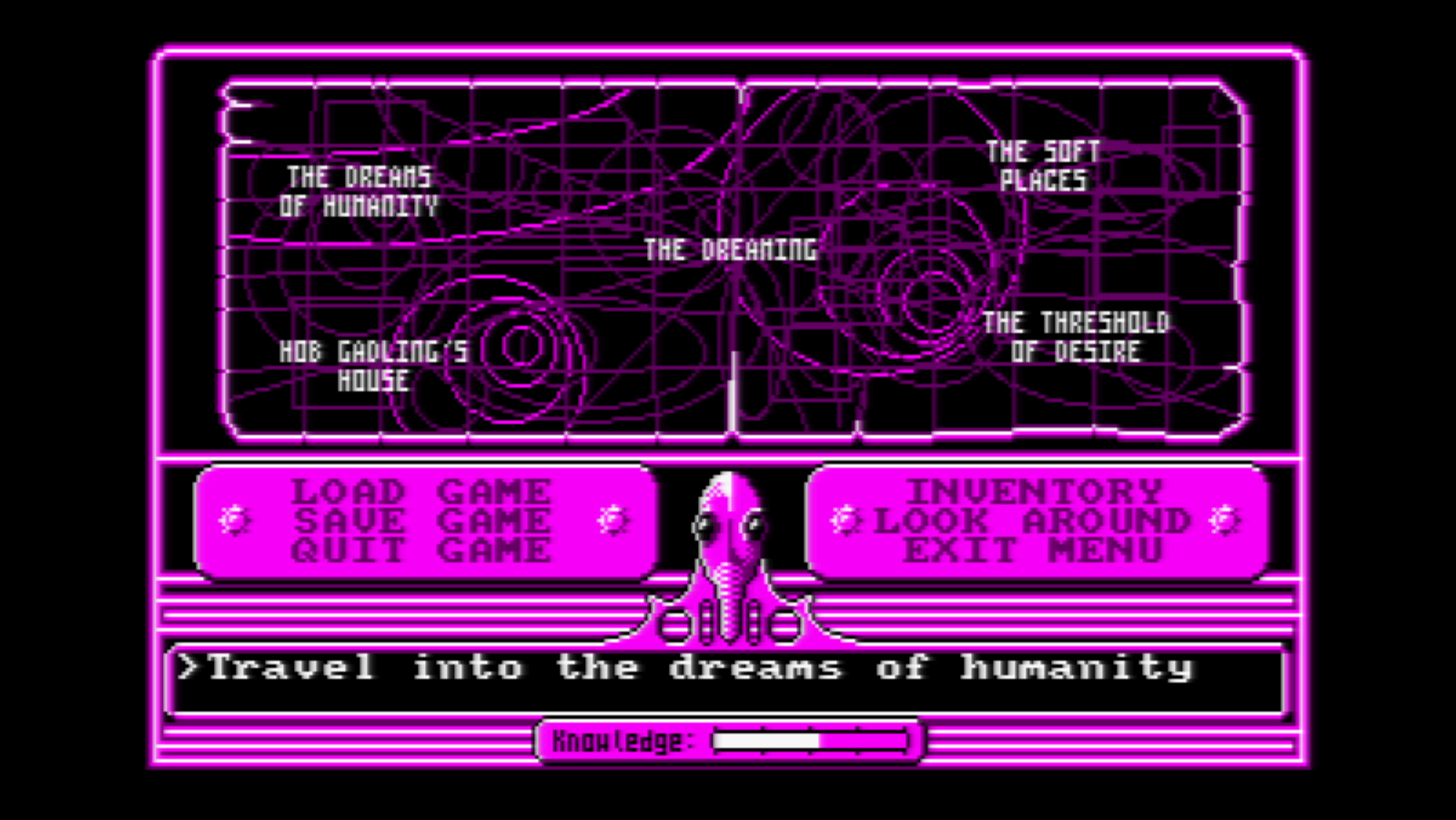

But even in the mid-90s, some coders were still beavering away on the old 8-bit microcomputers. And so, in 1995 on the Amstrad CPC, we got the first and so far only video game set in The Dreaming: The Sandman: Love and Magic, created in its entirety by the 19-year-old Ulrich Schreitmueller (aka The Electric Monk of TGS). This graphical text adventure finds Dream and Desire squaring off against one another over the stability of the dreaming world.

You travel through the dreams of humanity, to Earth, and across the Dreaming to gather the necessary knowledge to put Desire in their place. Along the way, you interact with many notable characters from The Sandman, including the Endless, Hob Gadling, Fiddler’s Green, Cain, Abel, Eve, and Matthew the Raven.

Love and Magic isn’t for everyone: even in 1995 this would have been considered archaic, playing it today requires patience, and a walkthrough is a necessity. But come at it with the right mindset and this is about as fine a Sandman game as you could hope for given the circumstances of its creation. Almost all the characters (particularly Dream) sound like their comics counterparts, despite the four-color palette the locations are instantly recognizable, and there are some very nice Easter eggs tucked away inside (you can visit Batman’s dream!)

How it happened

We spoke to Love and Magic‘s creator to ask him his thoughts on his game being unearthed 27 years on from its original release, how it came about, what he’d have done differently, and his feelings on how the Netflix show adapted Gaiman’s books.

Schreitmueller says The Sandman comics blew his mind, praising the Goth aesthetics, varied art style, and Gaiman’s writing:

“I was always a fan of mythology, and the sheer wealth of references floored me. For everything I recognized, there were three other things I didn’t. As I said, there was no readily available internet at the time, let alone anything like Wikipedia, so I found myself in my free time at school, reading the latest trade paperback, and stopping every few pages to run to the big encyclopedia in our school library to look up who Azazel or Geryon were. And it’s not just the references, it’s the whole style of the writing.

There are lines that resonate with me to this day. I can recite Etrigan’s “Back to your gate and duty, Squatterbloat” rhyme in its entirety. Abel’s “It’s only blood, little brother” still brings a tear to my eye, and “She… She has decided she no longer loves me” is just beautiful in its somber acceptance.”

Unfortunately, nobody else had even heard of The Sandman in his small rural town, but inspiration struck and he turned to the one computer he had access to, the Amstrad CPC (or as it was known in Germany, the Schneider CPC). He goes on to explain that:

“The game was written when I was 19. I was a shy, reclusive shut-in. I had one really close friend in school, I had a crush on a girl that I actually addressed as “milady”, I wore a long coat, a black turtleneck sweater and an Ankh necklace, and I thought myself incredibly deep, clever and mysterious.”

In our books, that makes Schreitmueller the perfect person to develop a Sandman game, though the end result of his labor seems to have primarily been the simple satisfaction of creation:

“In effect I had produced a game in an unpopular genre, on an obsolete computer, about a fringe segment of an already shunned type of literature, in another language.”

When Love and Magic was finished, he handed a few copies to friends (at least one of them even played it!) and that might have been the end of the story. But once the internet emerged it was uploaded to a few Amstrad FTP sites and was acknowledged as a late homebrew release in a history book about the system.

Now the game is reaching a wider audience. Schreitmueller posted about the game on The Sandman‘s Facebook page and got an “overwhelming” response from fans happy and surprised there was even a Sandman game at all.

Adapting The Sandman as a video game

We wanted to know what it was like tackling a property with so wide a scope, particularly as the characters don’t tend to engage in conflict in the traditional sense. Schreitmueller’s workaround was to not limit the player from doing anything, merely explain why Dream wouldn’t do it at that time:

“You have to keep in mind that whenever you play a being that’s essentially omnipotent, you essentially have to do two things: First, you need to limit the player’s powers somehow, otherwise you’d have to write a sandbox-like god simulator. So, instead of the game telling you “you can’t take the table” when the player tries to do so, it instead merely dissuades you with messages like “you don’t need to rearrange the furniture right now”.

Most contemporary developers would still struggle to develop a game with a figure as all-powerful as Morpheus as the player character. We asked how a Sandman game on modern hardware might look:

“I can’t really imagine Sandman as anything else than an interactive story. Sandman was never about action, so those genres wouldn’t be a good fit. Perhaps it might work as a role-playing game, but since so much of Morpheus’ character is defined by the fact that he doesn’t change, I don’t really see him squeezed into a system where he can level up hitpoints, spells and armor.

Perhaps a more feasible way to go would be to make the game about a character that isn’t Morpheus but merely interacts with the Endless, but my guess is that part of the allure for players is actually to slip into the skin of the Dream Lord himself. A multi-player open-world game where you align yourself with one of the Endless and do tasks for them?”

Perhaps an interactive story really is the best way to go, potentially in the style of the defunct Telltale Games or Supermassive Games’ Dark Pictures Anthology.

The Netflix show

To wrap things up we asked for Schreitmueller’s take on Netflix’s The Sandman. Unsurprisingly he’s “very very impressed”, having been following the live-action adaptation throughout its journey through development hell. Would he have done anything differently?

“Certainly. I think so would every fan. Would the show have been better? I doubt it. For example, I was adamant before the show that Dream NEEDS those dark eyes with the stars in them, as well as the chalk-white skin. Now that I’ve seen a few pictures of (incredibly good) Dream cosplayers, I realize that it would have made the character look far too outlandish. What works on a comic book page doesn’t necessarily work on screen.

Similarly with the level of violence. Sandman began as a horror comic, and a lot of the elements that were raw and edgy then now seem like shock for shock’s sake. Yeah, I wish they’d kept Alex Burgess’ “Eternal Waking” punishment sequence, but I’m glad some of the more gratuitous elements in “24 Hours” were toned down.”

If you want to play The Sandman: Love and Magic it can be downloaded for Windows machines here (right click, save as) in a relatively easy-to-use format. We’d highly recommend perusing the “2022 Readme” before starting, as if you’re not used to this style of game things will get confusing fast.

The Sandman is available to watch on Netflix now.

Published: Aug 16, 2022 11:30 pm