Hercule Poirot is famously methodical and meticulous, relying on logic, reason, and – as Tina Fey’s Ariadne Oliver enthusiastically notes while shadowing the detective during one of his many interrogations in A Haunting in Venice – “lists!” to solve knotty murder mysteries. By far the most interesting aspect of the famous Belgian detective’s third outing, through the lens of the increasingly assured Oscar-winning actor-director Kenneth Branagh, is the challenge that the spiritual world poses to his rational beliefs.

A Haunting in Venice, loosely based on Agatha Christie’s 1969 novel Hallowe’en Party, puts Poirot at the center of a fencing match between the physical and metaphysical worlds, playfully-yet-earnestly introducing a horror element to the star and filmmaker’s ever-growing (in both quantity and quality) mystery series.

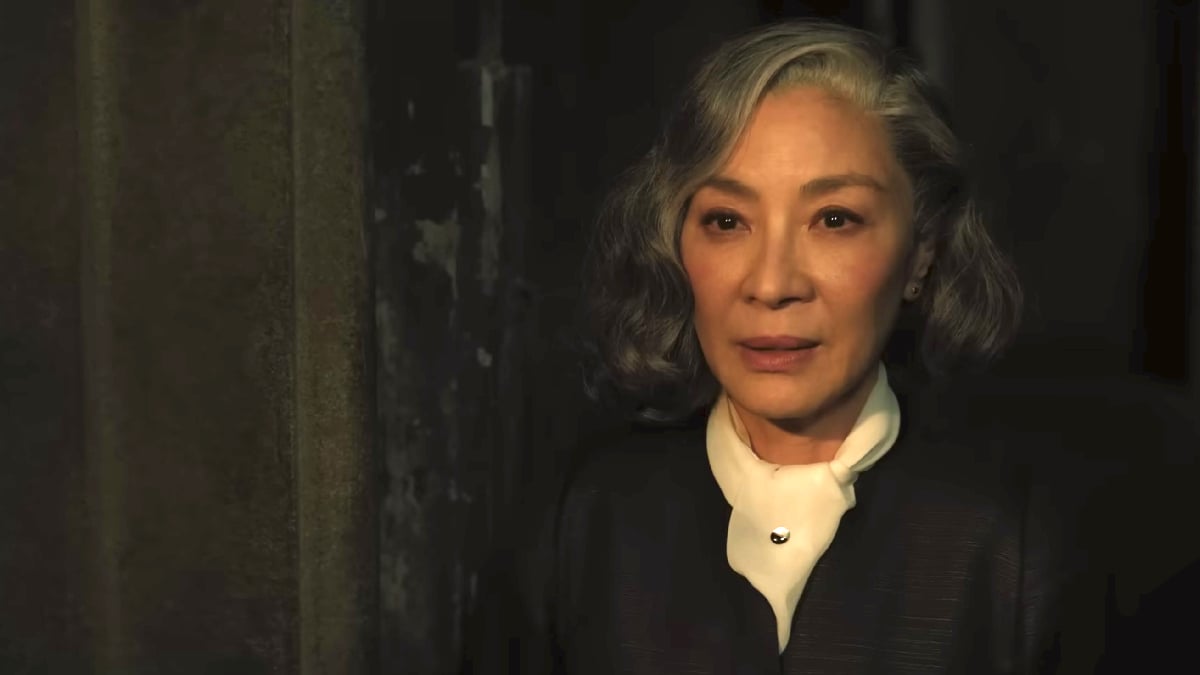

Our story begins on Hallows’ Eve, in the nooks and crannies of the most beautiful yet secretive city in the world: Venice. Poirot is approached by mystery novelist and long-time friend Ariadne to attend a séance, hosted by Kelly Reilly’s Rowena Drake in order to communicate with her diseased daughter, Alice (Rowan Robinson). The medium conducting it, Joyce Reynolds, is one of the most coveted in her profession, played beautifully if briefly by Michelle Yeoh. As a character, she’s a counterpoint to Poirot’s unbelieving nature, a bridge to a world he’s adamant does not exist.

Also attending the gathering are Alice’s standoffish ex-fiancé Maxime (Kyle Allen), the religious housekeeper Olga (Camille Cottin), the Drake family doctor Leslie (Jamie Dornan) and his off-putting son Leopold (Jude Hill), Poirot’s trusty bodyguard Mr. Portfoglio (Riccardo Scamarcio), and the psychic’s assistants Desdemona and Nicholas (Emma Laird and Ali Khan). The spiritual session takes place in a seemingly haunted palazzo, a former orphanage where children are said to have been locked up and left to die during the Black Death, and which the Drakes now own. The perfect scenario to raise the occult and to put a demotivated Poirot to the test.

The protagonist, tired and brought down by the constant presence of death in his life (whether through the murders he’s tasked to solve, or the two World Wars he’s had to live through), is challenged, here, to be the closest he’s ever been to the dead, speak directly to them, and even look them right in the eye. The hauntings, albeit questionable for reasons we will not mention in order to keep the mystery alive, force him to break out of his stupor and rethink his approach to his profession. It’s also a case challenging enough to ruffle his feathers and re-ignite his appetite for investigating.

Branagh’s directing does a mostly adequate job of exploring these complex ideas, creating – across most of its runtime – a genuinely intriguing and spine-chilling movie. The photography and production design stand out, even if occasionally leaning towards self-indulgence. They draw inspiration from noir and German Expressionism, skillfully employing light and shadow not only to establish the mood but also to reveal the characters’ most malevolent tendencies.

There’s a genuine attempt at elevating this third Poirot film, infusing it with a stronger and more refined creative vision, but Michael Greene’s screenplay is simply not strong enough to not be completely drowned out in the process. The ensemble is not particularly interesting, with the exception of Fey’s cunning writer and grafter Ariadne, who had great chemistry with Branagh/Poirot, as well as Cottin’s pearl-clutching housekeeper and Hill’s precocious Leopold, who also emerge as bright spots. The murder mystery itself is not much of a mystery at all, and although the horror elements add to its ambition, they also very much act like smoke and mirrors to hide a murder plot that, in the end, turns out quite basic. Time and time again, in an attempt to scare, threads are created that never get a resolution. The buildup is too great and too effective for such a bland and rushed conclusion, turning engagement and excitement into disappointment.

Still, it’s undeniable that director Branagh understands the dramatics of the genre as well as the city he chose to stage it in this time around. As the leading man and the audience’s window into the case he’s attempting to solve, he succeeds as a counterpoint to his perpetual rival, Sherlock Holmes, never diverting attention from the puzzle and toward himself. Intentionally or not, Branagh’s Poirot comes across as more subdued, less of a showman, which diminishes the character’s charisma but also aids the viewer in focusing solely on the task at hand; solving the murder.

A Haunting in Venice is the best in Branagh’s Poirot series by a long shot. It captures Venice beautifully, effectively exciting the viewer and raising interesting questions about the realms of the living and the dead. If anything, it’s a great movie to watch this Halloween, and a decent addition to both his body of work and the murder mystery genre.