Warning: This review contains spoilers for Belle.

Belle is Studio Chizu’s fourth film since Hosoda and producer Yuichiro Saito departed Madhouse and co-founded the “auteur’s studio” in 2011. And while Belle has been described many times over now as the “anime that [Hosoda] always wanted to make,” I can’t help but feel that the best parts of this film are the parts he mostly didn’t.

Belle is a spectacle, which is fitting given its vision of a new era of mass communication. In Belle, a depressed suburban girl enters the virtual social media world of U and becomes a global superstar through her singing. Or, her titular avatar does anyways, which does not look or sound like her. The songs aren’t entirely hers either, but the after-school project of a close friend that becomes her producer and manager. I’m sure there are ideas worth exploring there about auteurship and celebrity, but Hosoda doesn’t go there.

The social experience of U is the focus of Belle, which Hosoda tells Kotaku is a thematic sequel to his 2009 film Summer Wars (which he sees as itself a sequel to Digimon Adventure: Our War Game!). And it’s an oddly prescient film to have (first) released the same year Facebook announced the metaverse — because U is a virtual world, but also an alternate reality.

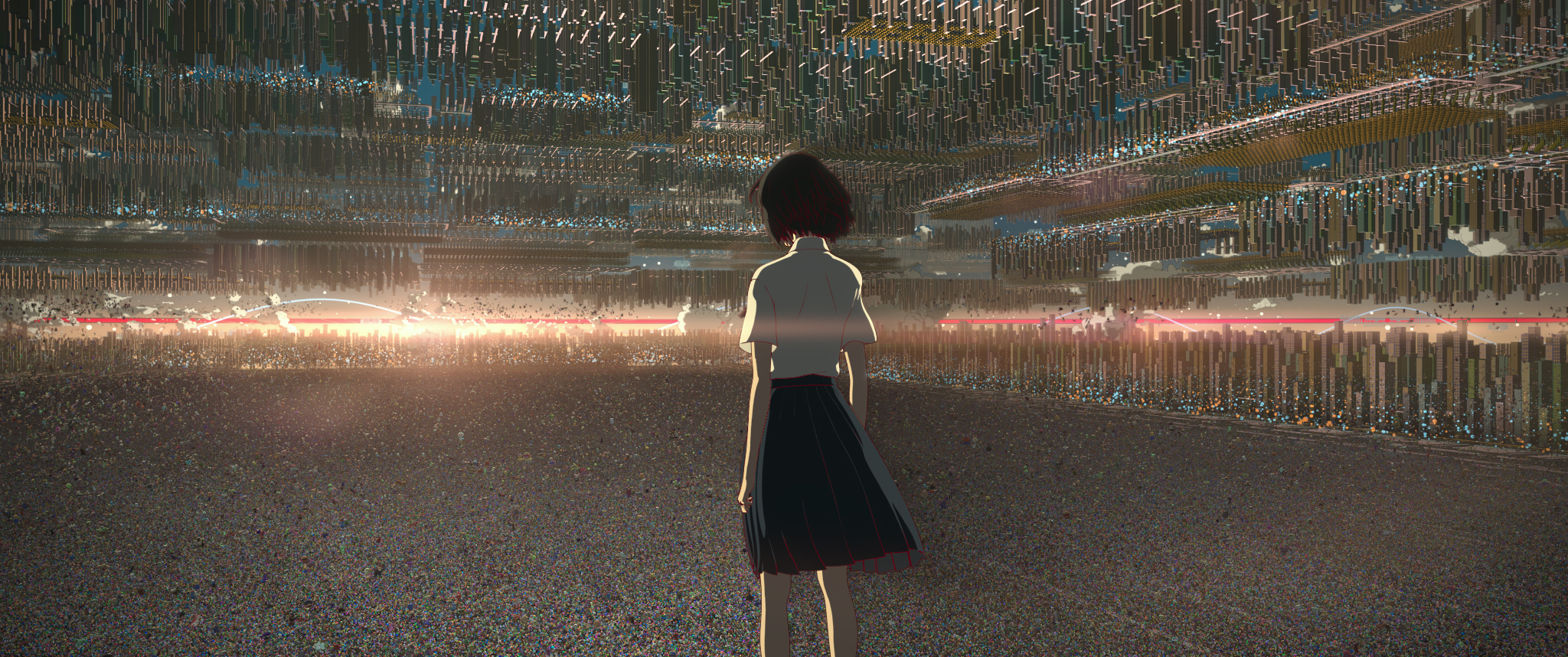

U is a sight to behold, and if you see it, I’d recommend a big, big screen. The design was conceptualized by Eric Wong, a London-based architect who imagines the internet in three dimensions, as a city where there is no up or down, no horizon; Inhabited by avatars that can take on the shapes and sizes of non-humans that look like they were each dressed by Oskar Schlemmer. It has more in common with Adventure Time’s surrealist Better Reality than something like the Matrix.

The synergistic international collaboration that gives U life is made better with Disney animator Jin Kim (Frozen), who designed the titular character. Wong’s designs and Chizu’s 3D animation are matched by the background art of Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart’s Irish animation studio Cartoon Saloon (Wolfwalkers, Late Afternoon), which create a fantasy setting within U.

By the end of Belle, however, I felt unfamiliar with their world and its characters. U always bends to the narrative, hardly constrains its agents. And it’s taken me some days to register this disappointment and find what it is I do appreciate in the film. Belle is caught between genres. In form, Belle is a real-kei. In content, it’s an isekai.

In Proto Anime Cut, historian Stefan Riekeles defines real-kei as “a form of science fiction anime involving realistic construction of possible worldviews and convincing visions of future cities and landscapes.” As such, these engage in architecture more than spectacular fantasy, trying to capture the scale of the world’s nascent megacities as they were being built. Concrete jungles — no, rainforests — whose landscapes materialized ideologies.

Real-kei is also part of what made anime a global phenomenon, it’s seminal film Katsuhiro Otomo’s 1988 adaptation of Akira. See also: Ghost in the Shell, Patlabor. These films can be defined by their cyberpunk cityscapes, from Tokyo (Patlabor: The Movie) to Neo Tokyo (Akira), to Neo-Tokyo 3 (Evangelion). And its visionaries were early adopters of 3D animation. Nowhere else is real-kei’s legacy more evident than in the production qualities of Rebuild of Evangelion (which concluded the same year Belle premiered in Japan).

U shares qualities with real-kei cityscapes — Hosoda imagines hierarchy and status in the virtual, the evolution of social capital and advertisements, how policing is stripped of any pretension of security in a world without the scarcity that drives people to crime — but Belle is largely unconcerned with these things.

Rather, U offers the main characters what is essentially a power fantasy, one that dabbles in fantasy tropes and settings. It’s an isekai, “different-” or “otherworld.” And there is something to these seemingly antithetical genres coming together that I think could capture the contradiction we are all struggling to live right now, as the virtual becomes more real and third spaces are both digitized and privatized.

Unfortunately, U bends to the narrative. And Belle’s story is always its least interesting part.

Warning: Spoilers regarding Belle‘s plot to follow.

In places, it feels like Hosoda just doesn’t bother with characterization. You better already be rooting for the boy and girl to get together because this is a fairy tale pastiche and the boy and girl have to get together — Hosoda won’t give you any other reason to think that they should. I don’t even remember Suzu’s love interest’s name.

The narrative is also presented in a nonlinear fashion, which feels like scrolling back through a timeline ordered chronologically, but with threads and comments bouncing around time. And as it so often does, I felt like I was missing something. The choir ladies, for instance, have an outsized role in Suzu’s life that is so unremarked upon that their presence on the screen feels awkward. Why are these women with these high schoolers?

I haven’t even talked about the parental abuse plot that shows up in the final 20 minutes and somehow bends Suzu’s character arc to its conclusion. It’s bad, possibly infuriating. I am going to stop thinking about it.

With U, Belle could be a prescient reimagining of real-kei for a new age, but it never fully escapes the tired conventions of homage it so desperately wants to fit into this future.

Belle releases in U.S. and Canadian theaters today (Jan. 14). It is screening in both English and Japanese.

Published: Jan 14, 2022 04:28 pm